A first-of-its-kind technology platform launching today allows legal researchers to examine large collections of historical texts to help determine the meanings of words and phrases in the contexts in which they historically were used.

The Law and Corpus Linguistics Technology Platform was developed by BYU Law in Provo, Utah, which is introducing it today to coincide with Constitution Day, which commemorates the signing of the Constitution.

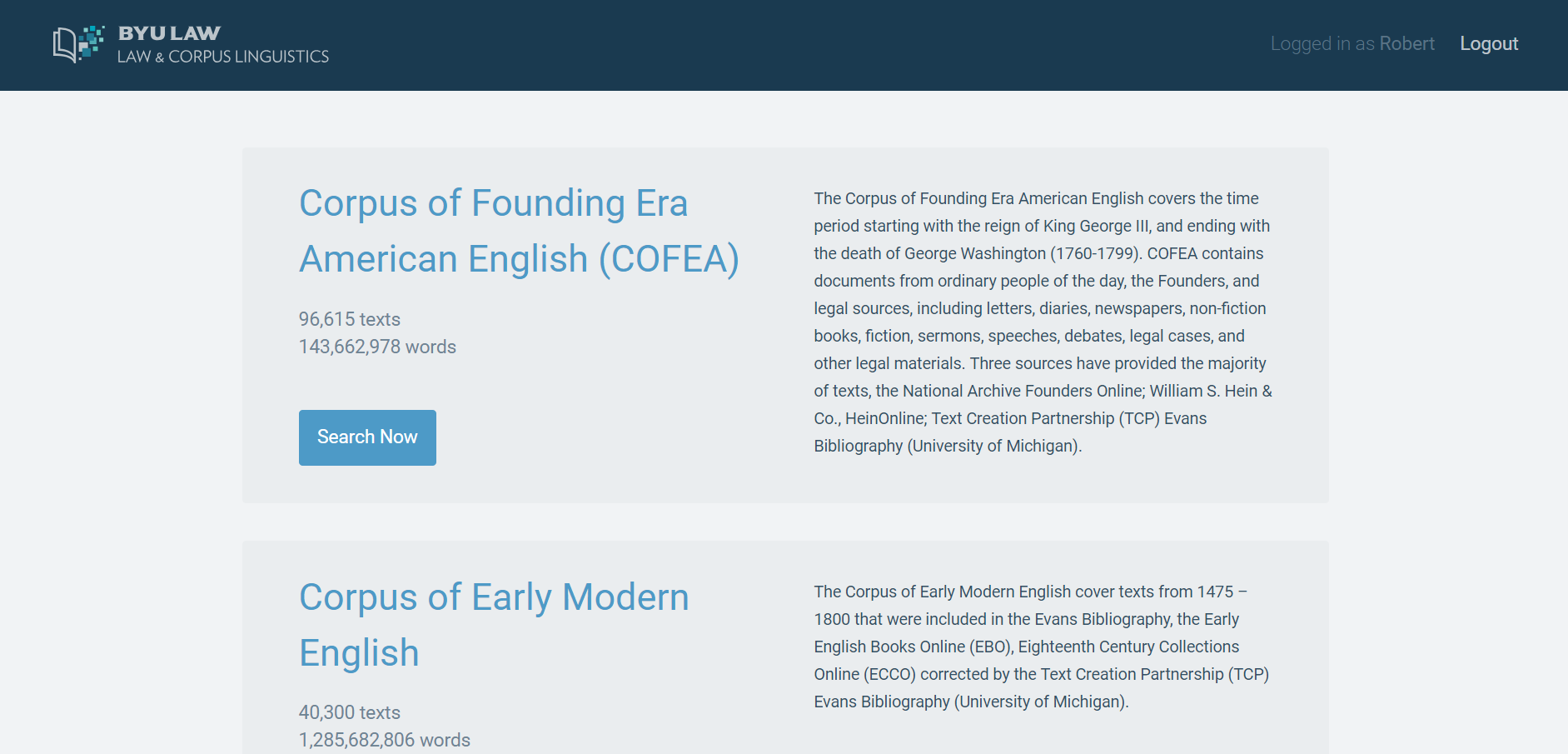

The platform is launching with three primary text collections, or “corpora”:

- Corpus of Founding Era American English, a collection spanning 1760 to 1799 that contains nearly 100,000 documents from the founders, ordinary people and legal sources, and that includes letters, diaries, newspapers, non-fiction and fiction books, sermons, speeches, debates, legal cases and other legal materials.

- Corpus of Supreme Court of the United States, a collection of all Supreme Court opinions in the United States Reports though the 2017 term (with the 2018 soon to be added).

- Corpus of Early Modern English, a collection of texts from 1475 to 1800 that were included in the Evans Bibliography, the Early English Books Online (EBO), Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) corrected by the Text Creation Partnership (TCP) Evans Bibliography (University of Michigan).

BYU Law has been developing the platform for some time – I first wrote about it last March in a post at Above the Law about technology innovation at BYU Law – but today’s announcement marks its official release to the public. The platform is open to anyone to use at no cost.

The BYU Law platform was inspired by the work of BYU linguistics professor Mark Davies, who pioneered the development of a variety of corpora at corpus.byu.edu. Based on Davies’ work, BYU Law Dean D. Gordon Smith decided to pursue development of a platform designed to serve scholars, judges and practitioners in the legal field.

As I wrote in another Above the Law column, the BYU corpora received a high-level acknowledgement in June when Justice Clarence Thomas cited them in his dissent in Carpenter v. United States, which held that the government’s acquisition of cell-site records is a Fourth Amendment search. Thomas argued that the phrase “expectation of privacy” never appeared in any papers of the founders, early congressional documents, early American texts, or early American newspapers. As his source for that, he cited the BYU corpora.

As I note in that same column, corpus linguistics has also been used in other appellate opinions and was formally endorsed by the Michigan Supreme Court in the 2016 case People v. Harris, which used the BYU corpus to interpret the word “information.”

How it Works

Last week, Dean Smith walked me through a demonstration of the new Law and Corpus Linguistics platform. Using the Corpus of Founding Era American English, or COFEA for short, he showed me how the platform could be used to explore the meaning of the phrase “bear arms.” (I later logged in on my own and replicated his search, and also performed some other searches of my own.)

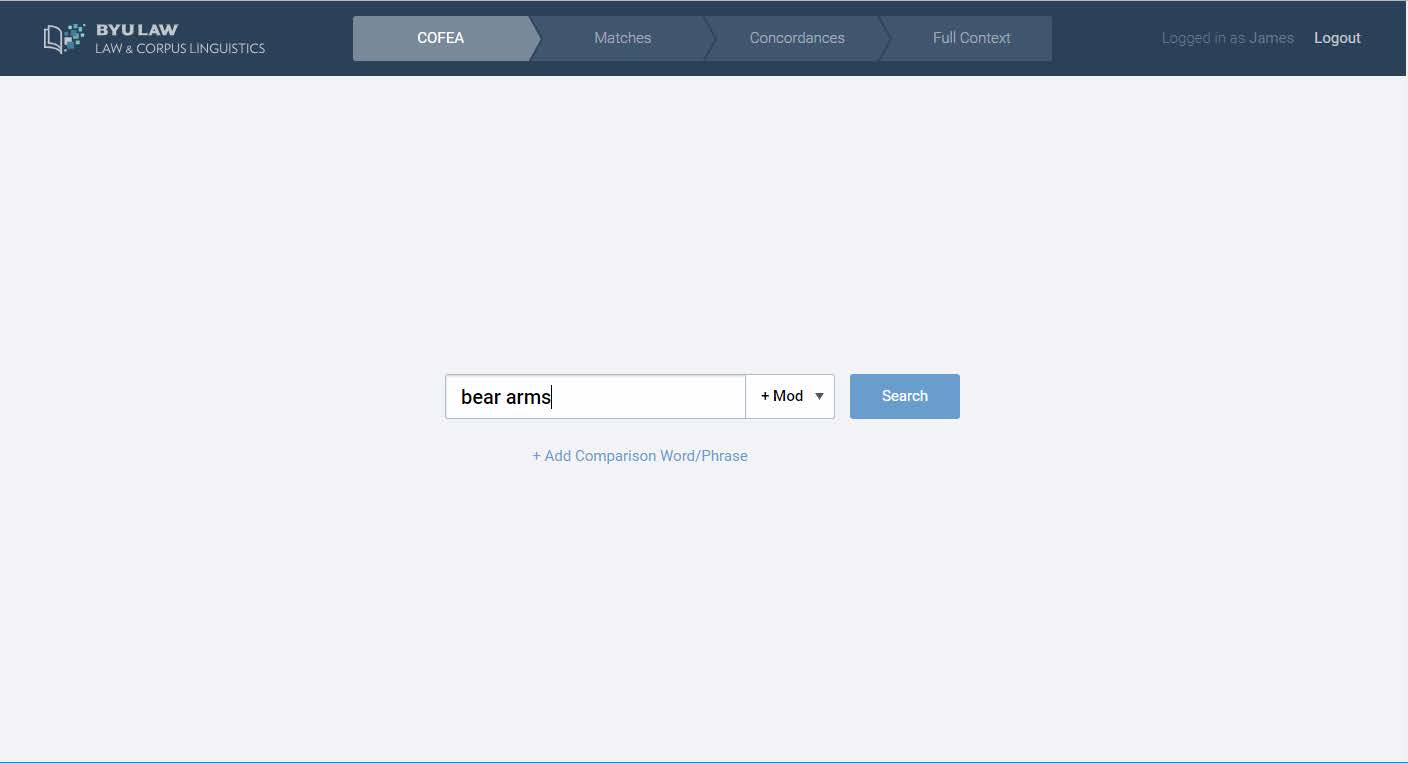

The initial search screen mirrors Google in its simplicity. Simply enter a word or phrase and then hit search. If you wish, you can limit queries by parts of speech (such as only adjectives). Had the search phrase been entered with brackets around it, it would also have shown variations. Thus, for bear arms, it would also show “bearing arms,” “borne arms” and “bore arms.”

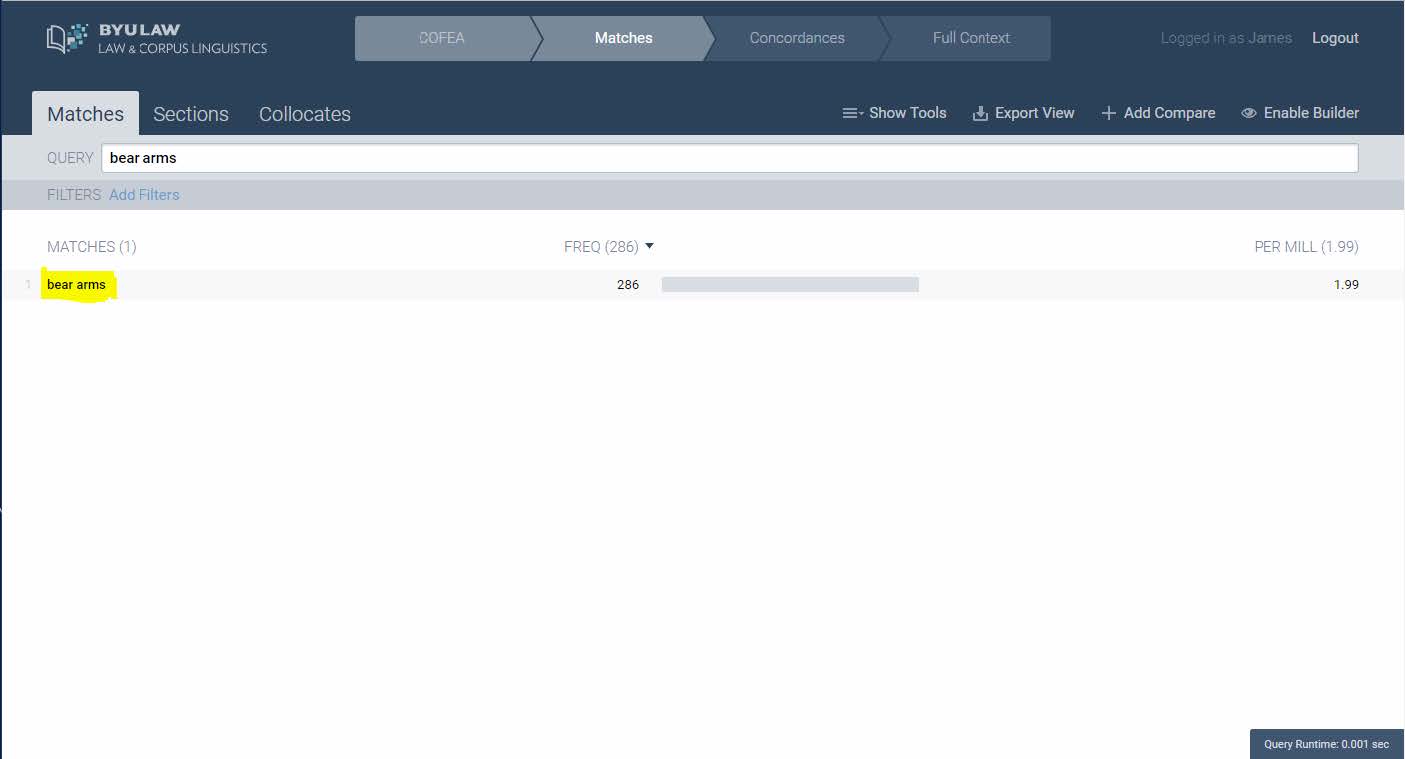

The search of the phrase bear arms reveals 286 occurrences within the corpus. This can be further refined to show the numbers of occurrences by year, decade, source or primary author.

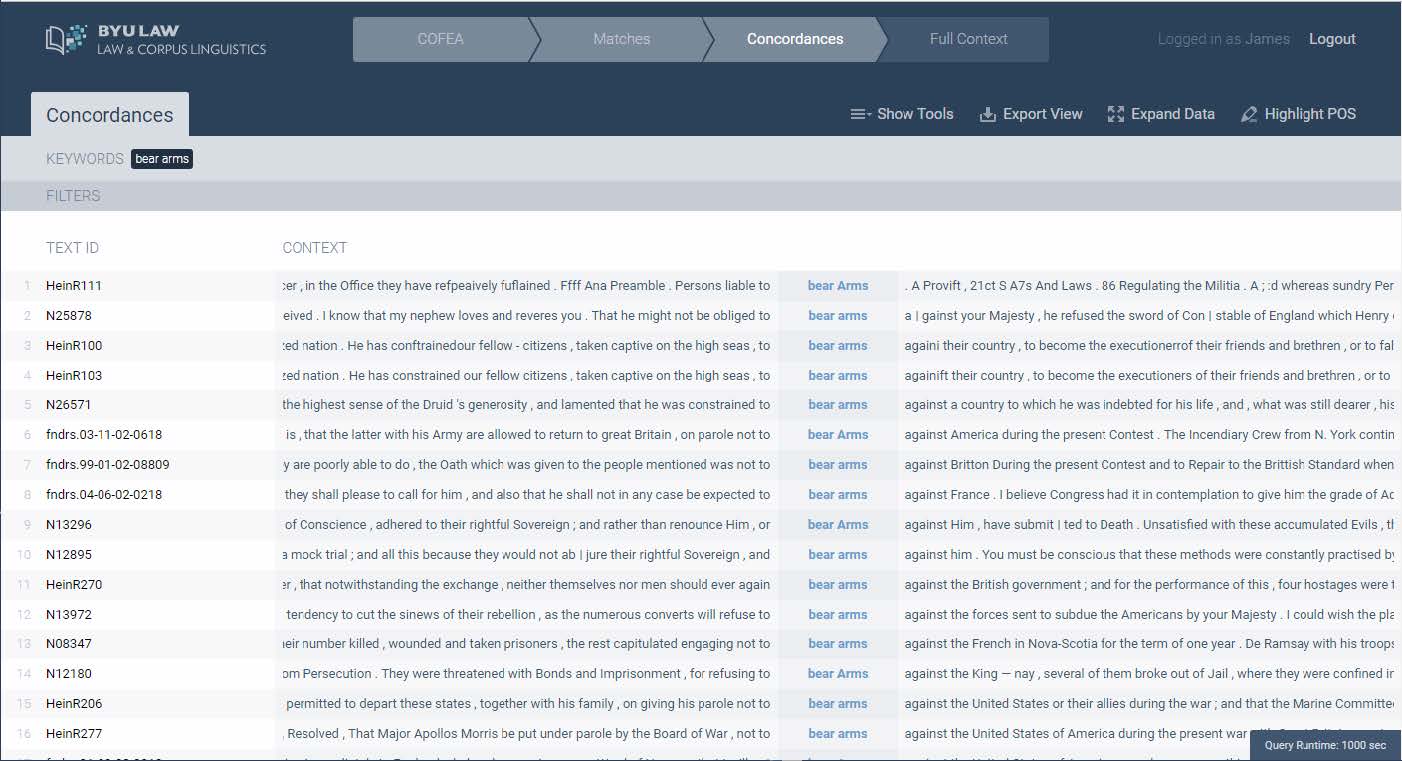

Having searched “bear arms,” you can now click on that phrase in the search results to display concordance lines. This is a page that shows all the occurrences of the phrase within the limited context of the words immediately before and after it. These results are arranged by the letter of the first word after the phrase you searched.

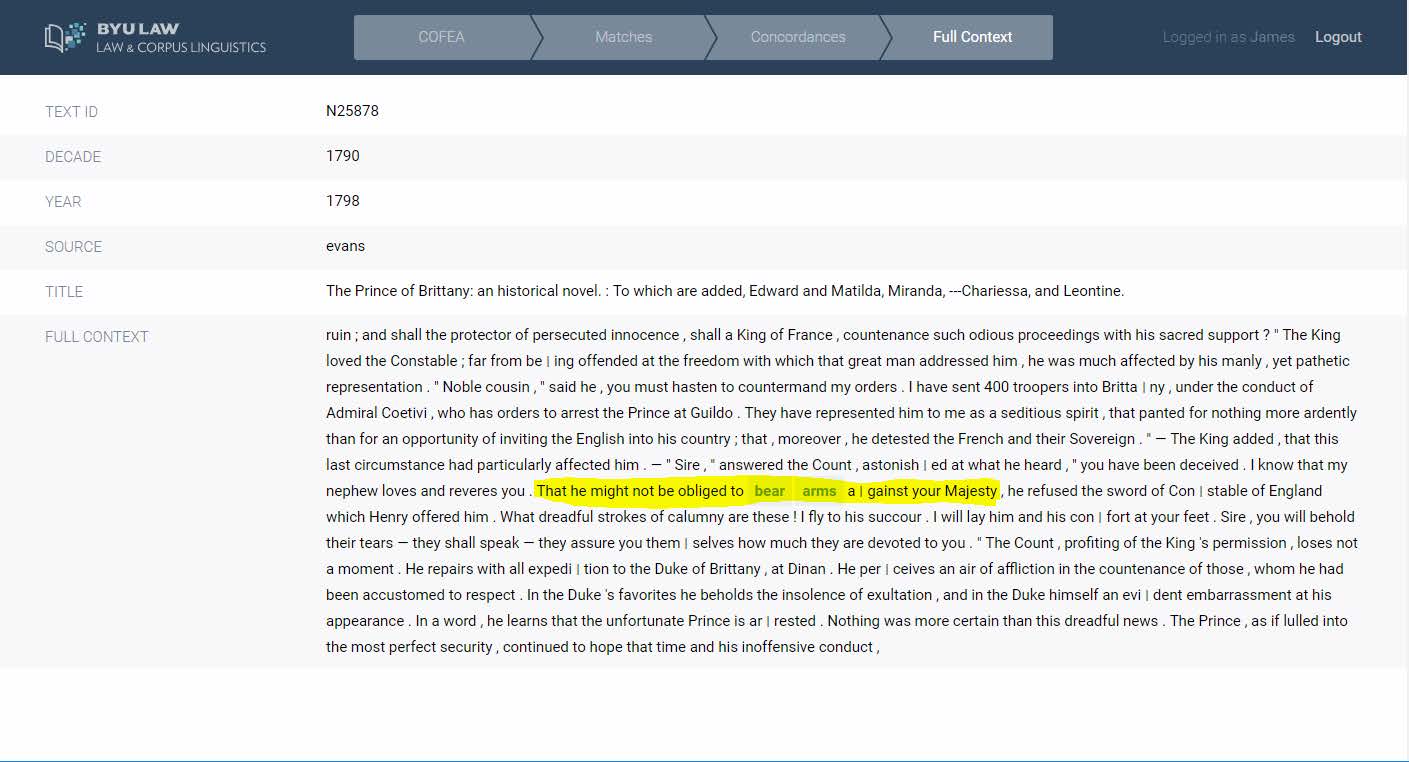

To see the full context in which the phrase appeared, click on any of the snippet lines. That takes you to a screen showing the full text and information on its date and source. From there, you can click again to view the original source document. While linguistic corpora do not typically include source documents, Smith said he thought it would be important to include these for the purposes of legal research.

“It’s interesting when you search a word to see the words that it hangs out with,” Smith said during our demo.

Much of the debate around the Second Amendment focuses on whether the right to bear arms is intended to relate only to a militia or also to an individual right, Smith said. When you look at the historical context, “bear arms” occurs most frequently with the word “against” – as in against a sovereign – and that most references are in the context of bearing arms “for the common defense.” But there are also references to bearing arms “for the defense of themselves and the common state.”

This demonstrates that corpus linguistics does not always provide clear answers, Smith says, but it provides empirical evidence that can be used to back up an argument.

“Some people think that this is a magic machine that will crank out an answer,” Smith said. What it does, he says, is give judges, lawyers and scholars better evidence that they can use in their opinions and briefs.

Another tool within this platform shows the collocates for the search phrase – the words that most commonly appear with it. As you might expect, the most-common words are not very interesting from a research perspective: “to,” “the,” “and” and the like. But the platform allows you to set what is called the mutual information score to display collocates with stronger connections to the search phrase. If you set this to 4, for example, then the most common collocates become “able,” “against,” “country” and “defence.”

More to Come

Having spent a couple of years building this platform and the corpora it includes, Smith said he is happy with the search engine and interface. At the same time, he believes it will be another three years before the platform is fully where he wants it to be, both in terms of the materials it includes and the features it offers.

At the same time, it is now easy to use this platform to create new corpora, providing the materials are available digitally, and he foresees this being used for a range of scholarly and legal research purposes.

So how can legal practitioners use this? Smith points to several potential uses:

- In judicial decisions, for better understanding of the meaning of words at the time documents such as the Constitution were written.

- In legal briefs, for lawyers to provide better evidence of the meaning of words and phrases.

- For statutory interpretation.

- For contract interpretation.

- For any situation involving the resolution of ambiguities in legal language.

As I said above, there is no cost to use the Law and Corpus Linguistics platform, so give it a try for yourself.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog