Here’s an idea: What if there was a way to promote access to justice while having fun at the same time? That is the idea of a unique project launching today that uses a game to train a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm ultimately will be used to better match those in need of legal help with the lawyers best suited to help them.

The game, called Learned Hands, is a joint project of Suffolk Law School’s Legal Innovation and Technology Lab, led by David Colarusso, and Stanford Law School’s Legal Design Lab, led by Margaret Hagan, with funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts. Colarusso gave me a preview of the project last week and allowed me to log in and try it for myself. This morning, he published a detailed description of the project at Lawyerist.

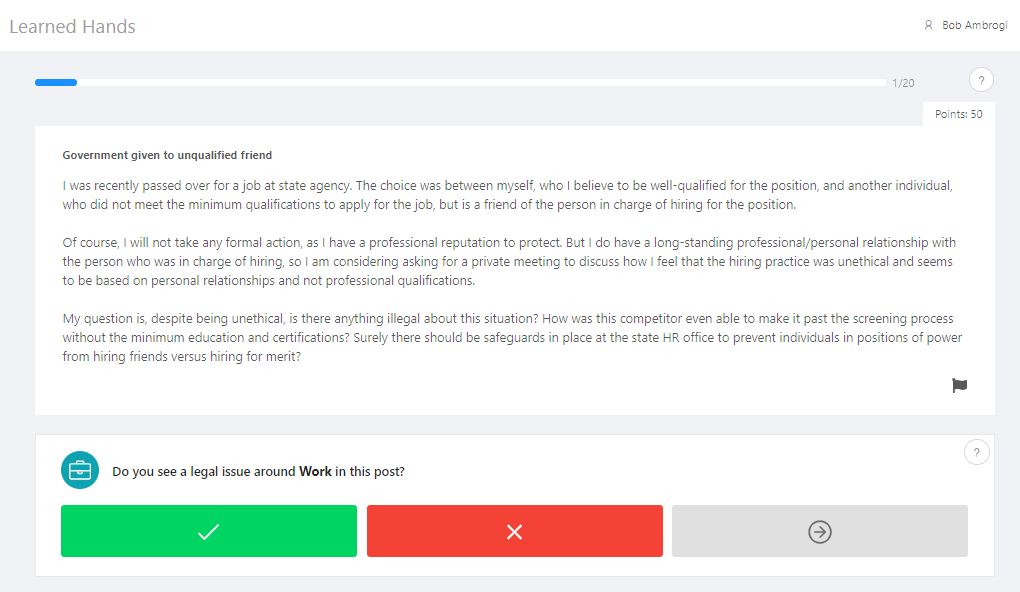

Players are challenged to spot the legal issues in real people’s stories about their problems. They earn points and rankings based on how many questions they mark and the extent to which their markings are deemed to be correct.

What is actually going on here is an attempt to use crowdsourcing to train an algorithm to spot legal issues in the words that ordinary people use to describe their legal problems. The goal is to develop artificial intelligence that will more accurately recognize the area of law involved in a legal question and therefore be able to better match the questioner to the appropriate attorney or legal resource.

There are two prongs to this project:

- Create a taxonomy of legal help issues. Hagan and her team at Stanford are taking the lead on creating a taxonomy that covers people’s common legal issues and questions. The idea is to develop a taxonomy that fits with the words and phrases regular people use when talking about legal problems. The end goal is to be able to use AI to match lay questions to the taxonomy and also match legal services providers to the taxonomy.

- Train the machine learning algorithm. To train the algorithm, someone needs to review thousands of lay questions and tag them to the taxonomy. For Colarusso and his team at Suffolk, that raises two hurdles: Where to get all those questions and where to get the personpower to tag them all. For the questions, the project found a ready source in the Reddit forum r/legaladvice, where the moderators agreed to share the collection of some 75,000 questions. As for how to tag them all, that is where Learned Hands comes in.

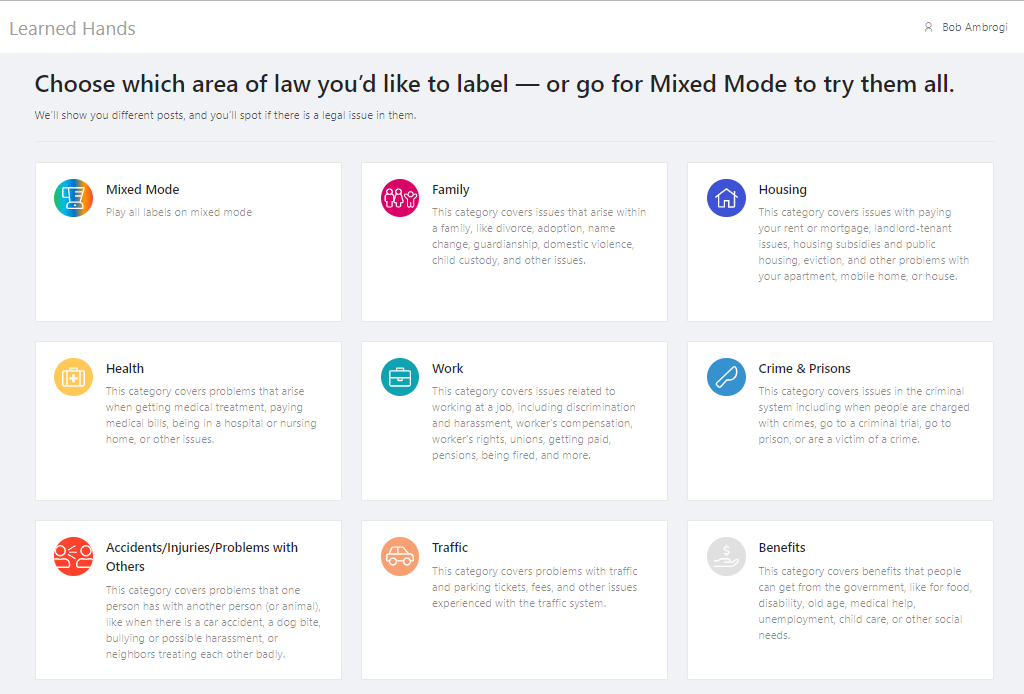

To play, you must first register, either by using a social media profile or creating a unique account. You need not be a lawyer or have any legal training to participate. After registering, you come to a screen that asks you to choose the area of law you’d like to label, or you can pick Mixed Mode to try them all.

I started with work issues and was presented with a Reddit user’s question and then asked if I saw in it a legal issue around work. I did, so I clicked the green check box. Once I did, I was presented with another user’s question and again asked if I saw a work issue.

As others play, these “votes” will be combined to determine whether an issue is present. The final determination of whether an issue is present is based on statistical assumptions about the breakdown of voters. If everyone agrees on the labeling, the final answer can be called with fewer votes than if there is disagreement.

This means that the utility of the next vote changes based on prior votes. The project uses this fact to order the presentation of questions, making sure that the next question someone votes on is the one that’s going to move it closer to finalizing a label.

Players earn points based on how many questions they mark (with longer texts garnering more points). They are then ranked based on the points they’ve earned times a quality score, which is a score measuring how well the player’s markings agree with the final answers.

What do you win? Pretty much just bragging rights as being among the best issue spotters. Plus you get the satisfaction of doing something for the greater good. The site will include a leader board and users will be able to sign up for weekly updates on their standings.

Assuming this gains traction, the project will eventually create a set of labeled data that it will make available to researchers at no cost, in the hope that they will use it to create useful tools to address access to justice.

As to how this data might be used, Colarusso’s Lawyerist post gives two examples:

- On a site such as ABA Free Legal Answers, where legal questions sometimes go unanswered because it is hard to match them to attorneys with relevant expertise.

- On a court website, to better use people’s own words to match them to the right legal resource, without requiring them to navigate legal terminology.

For Learned Hands to achieve its goal, it will need a couple hundred active players over the course of the next year, Colarusso said. I’ve written before about the difficulty legal-crowdsourcing sites have had in achieving critical mass.

But Colarusso believes this gamification approach will better incentivize people, as well as the fact that they can do it on their mobile devices. He recalled his prior days as a criminal defense lawyer, spending hours at a time just waiting in court for a case to be called. He would have been happy, he says, to have filled that time “making a contribution.”

As of this morning, the game is on, so try it for yourself.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog