With both Arizona and Utah now allowing nonlawyers to deliver legal services through alternative business structures, the American Bar Association today issued a formal ethics opinion that addresses the question of whether lawyers outside those states may passively invest in an ABS.

The issue hinges on ABA Model Rule of Professional Conduct 5.4, which prohibits lawyers from sharing fees with nonlawyers or practicing in an entity in which a nonlawyer has an ownership interest.

Last year, Arizona eliminated Rule 5.4, allowing the certification of ABS entities to deliver legal services. Also last year, Utah launched a pilot “regulatory sandbox” in which licensed ABS’s may include nonlawyer owners in firms providing legal services.

For potential lawyer-investors outside Arizona or Utah, these new forms of legal services entities raise the question: If the state in which the lawyer is admitted still adheres to Rule 5.4, may the lawyer passively invest in an ABS?

The answer, today’s opinion says, is yes, but with some provisos.

Just as a lawyer, outside the scope of the lawyer’s practice, may privately invest in any form of business, mutual fund, or security, a lawyer may invest in an ABS, the ABA says in Formal Opinion 499, Passive Investment in Alternative Business Structures.

But equally true is that, if the lawyer’s private investments create a conflict of interest involving the lawyer’s clients, then the lawyer would need to comply with the disclosure and writing requirements of Model Rule 1.8.

Similarly, if a lawyer invests in an entity that is a client or accepts an interest in a client’s business as a fee, the lawyer must again comply with Model Rule 1.8.

A second consideration, the ABA says, is choice of law: Which jurisdiction’s ethics rules apply to the lawyer’s investment activity, those of the lawyer’s home state or those of the state where the ABS is licensed.

Under the Model Rules, if the lawyer’s conduct relates to a matter pending before a tribunal, then the rules of the state where the tribunal is located govern. But in other cases, the applicable rules are those of the state in which the lawyer’s conduct occurs. In the case of an ABS investment, the conduct occurs in the state in which the ABS operates.

“When the Model Rule Lawyer is passively investing, the only relevant ‘conduct’ and the only meaningful ‘effect’ of that conduct occurs in the ABS-permissive jurisdiction,” the opinion says, discussing its hypothetical “Model Rule Lawyer.” “As to that conduct, the Model Rule Lawyer’s passive investment does not violate the rules of professional conduct of the ABS-permissive jurisdiction.”

However, in order to avoid any suggestion that the lawyer-investor is practicing law through the ABS, the lawyer must ensure that the ABS does not identify the lawyer as a practicing lawyer associated with the ABS.

The lawyer must also be careful to avoid conflicts of interest that could arise from representing clients in the lawyer’s home state.

“Such a conflict would exist if the Model Rule Lawyer were to act as an advocate against a client of the ABS or represent a business in a transactional matter requiring negotiation with a client of the ABS,” the opinion says.

In its conclusion, the opinion says:

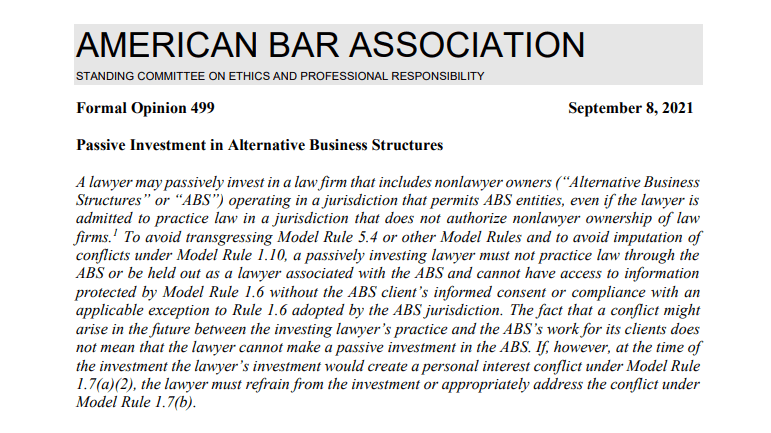

“A lawyer admitted to practice law in a Model Rule jurisdiction may make a passive investment in a law firm that includes nonlawyer owners operating in a jurisdiction that permits such investments provided that the investing lawyer does not practice law through the ABS, is not held out as a lawyer associated with the ABS, and has no access to information protected by Model Rule 1.6 without the ABS clients’ informed consent or compliance with an applicable exception to Rule 1.6 adopted by the ABS jurisdiction.”

Here is the full text of ABA Formal Opinion 499, Passive Investment in Alternative Business Structures.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog