Despite its name, Judicial Brief Analysis, an enhancement introduced today to the Lexis+ legal research platform from LexisNexis, is targeted at lawyers, enabling them to analyze up to six briefs at a time and receive a report comparing all case law, arguments, citations and quotes.

The product’s name is meant to suggest that it mirrors the process of judges and court clerks when they must analyze multiple briefs submitted by opposing counsel in a matter.

Judicial Brief Analysis builds on the Brief Analysis feature that LexisNexis introduced last year when it launched Lexis+, its premium legal research service. That was LexisNexis’s answer to a line of products pioneered by legal research company Casetext with its CARA brief analysis tool and followed by companies such as Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg Law.

The product launched today is similar to one that Thomson Reuters introduced last year, Quick Check Judicial, which similarly built on TR’s previously introduced brief-checking tool, Quick Check, to allow a user to upload multiple briefs in a matter and compare them against each other.

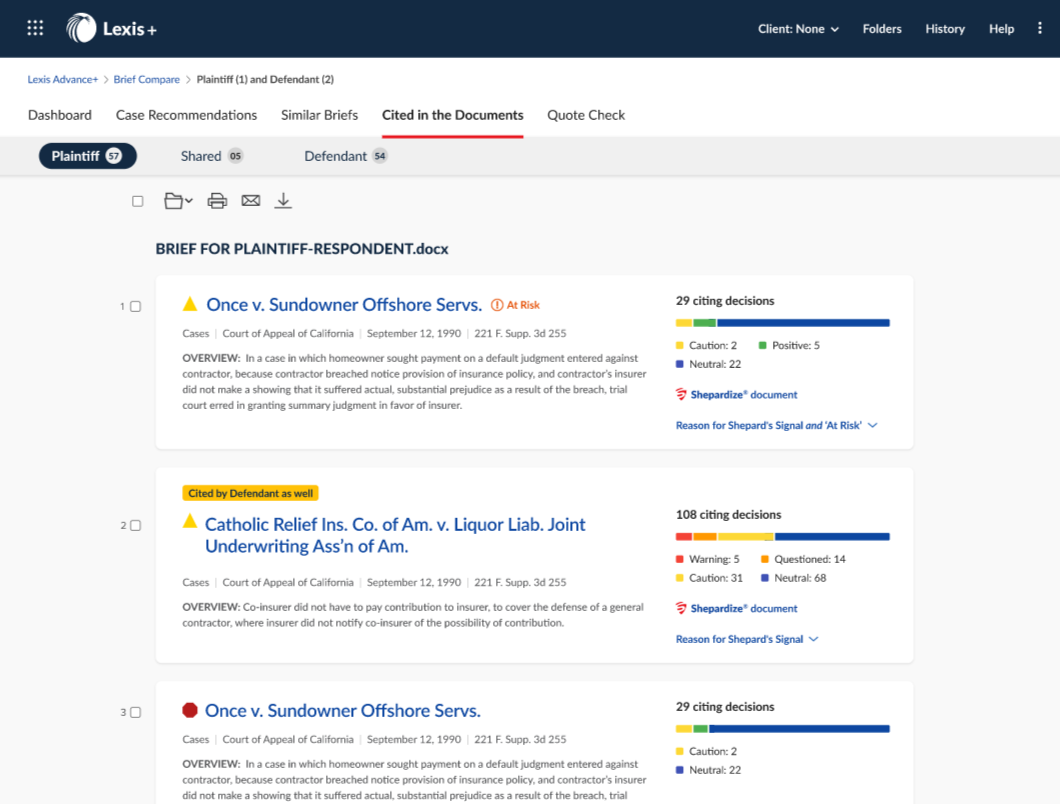

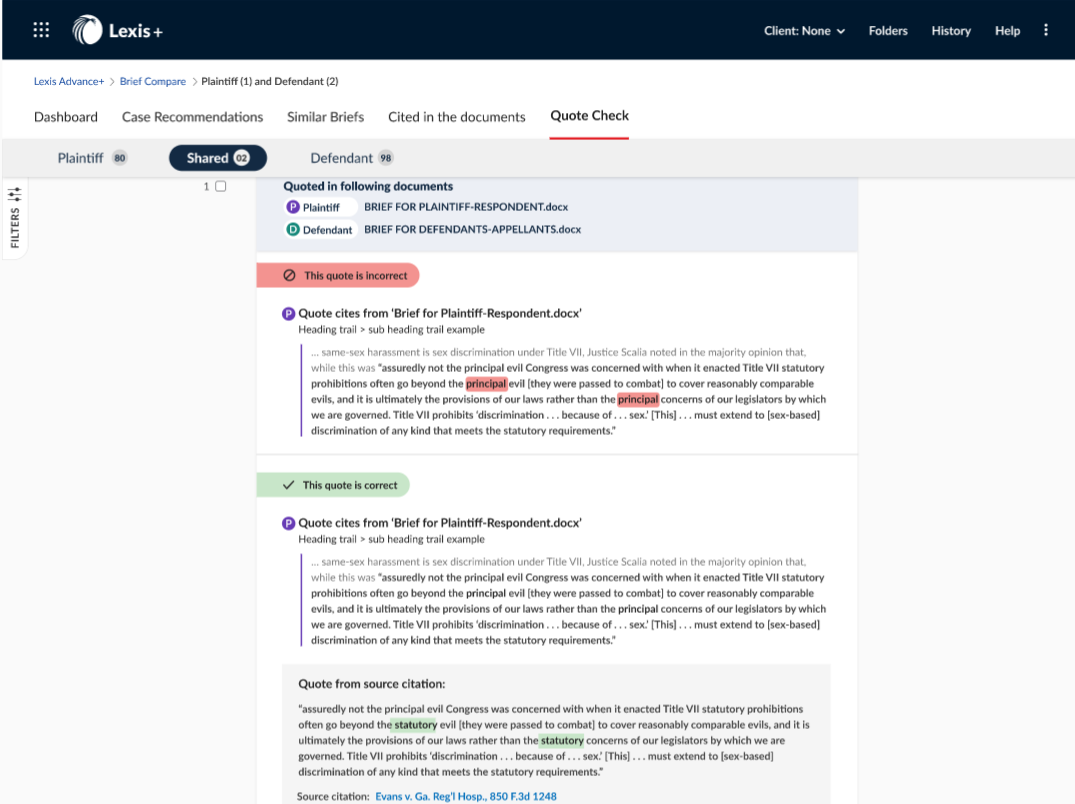

Like that product, Judicial Brief Analysis allows a user to see all the cases cited by both parties in common, all the cases cited by only one party or the other, and relevant cases and authorities cited by neither party, as well as Shepard’s warnings and quotation checking (checking to see if a quotation from a case is accurate).

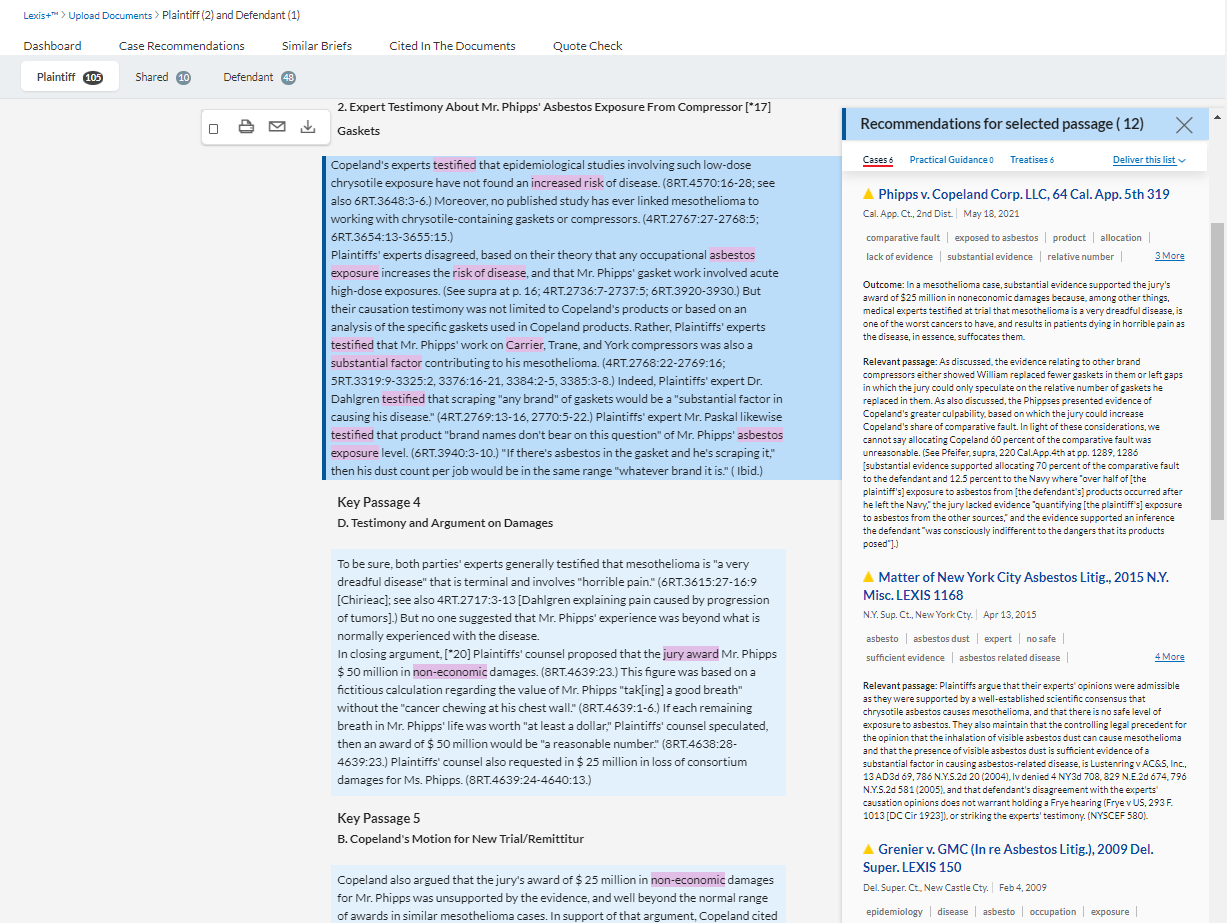

The tools extracts concepts from a brief and offers recommendations of relevant cases and treatises.

LexisNexis says Judicial Brief Analysis can compare up to six briefs total — which it somewhat confusingly says means three for each side. I am not sure how often a single party files three briefs in conjunction with a specific motion or matter. And what happens when there are more than two parties, such as when there is a third-party defendant?

During a demonstration of the product last week, I put that question to Elizabeth Christman, product manager for case law at LexisNexis. She said that it does not actually matter which side the briefs are for, as long as they are for the same matter with the same case heading.

But the problem, it appears, is that the product can compare only two parties, which it designates as plaintiff and defendant. So if there are more than two parties in a matter, it appears the user would be able to compare just two sides at a time. (The same is true, I believe, of the Thomson Reuters Quick Check Judicial product.)

Dashboard View

Similar to other brief-analysis tools, a user starts by uploading the briefs to be compared. They can be in Word or PDF format.

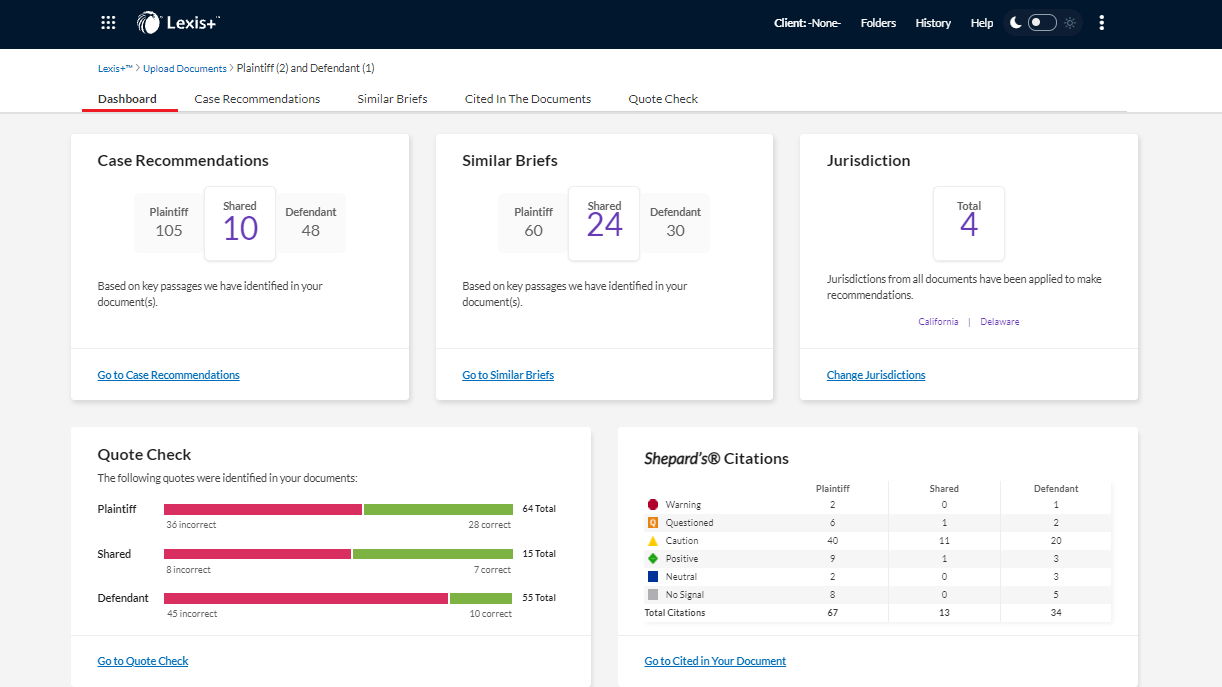

Once the briefs have been uploaded, the product extracts and analyzes citations and concepts in the documents and shows the results in the dashboard, which provides a visual overview of the results, both for each side separately and for the results that both sides share in common (as shown in the featured image above).

The dashboard shows the number of additional cases it recommends as potentially relevant, how many similar briefs it has found, the number of jurisdictions from which relevant documents have been found, the accuracy of case quotations in the briefs, Shepard’s Citations, and extracted concepts.

From the dashboard, a user can move through tabs to see specific recommendations for recommended cases, similar briefs, analysis of cases cited in the documents, and accuracy of quotations.

Within each tab, the user can select to view the analysis for just one side or the other, or the user can select the Shared view, which shows the analysis and recommendations for cases and quotations the two sides’ briefs have in common.

The tool also extracts and identifies concepts in briefs and maps those concepts to recommend other resources that may be relevant, including treatises and practice guides. Christman said that it can find similar concepts even when they are expressed using dissimilar words. For example, she said it would know that seatbelt and safety restraint are similar concepts, even though they are different words.

The tool does not currently allow a user to click through from the analysis of a document to the full text of the document. Christman said that is on their “to-do” list for a future release.

A Safety Check for Your Briefs

The two primary uses of a tool such as this are to check your own brief before filing it or to check your opponent’s brief after you receive it.

Among the advantages of comparing both sides’ briefs at once is that you can see the potential weaknesses and holes in your own brief — and thereby address them — while also, at the same time, seeing the weaknesses in your opponent’s brief and the cases your opponent disregarded or overlooked.

LexisNexis did not provide details on the cost of Judicial Brief Analysis.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog