Just four years after launching Westlaw Edge as its next-generation legal research platform, Thomson Reuters today unveiled the next-next generation. It is called Westlaw Precision and, as the name suggests, its focus is on delivering research results that are more precise than ever before, and delivering them with greater speed than ever before.

What does TR mean by more precise? It means search results that better match not just the legal issue, but also the outcome, fact pattern, cause of action, motion type and outcome, party type, and area of law.

And in a moment when AI-driven research is all the rage, Precision takes a somewhat old-school approach to achieving this precision — using hundreds of lawyer editors to manually tag cases with greater granularity than Westlaw had previously done through its Key Number System (while by no means abandoning the advanced AI that helped power Westlaw Edge).

“For more than 100 years, we have classified legal issues with the West Key Number System,” Leann Blanchfield, head of primary law, editorial, said in a statement. “Now we are also classifying cases by issue outcome, fact pattern, motion type, motion outcome, cause of action, and party type. This enables customers to specify precisely what they want and retrieve it quickly.”

Advance testing of Westlaw Precision among 101 lawyers found that just 10 minutes into a research session, the lawyers had found three times as many relevant cases, TR says. Nearly all those lawyers said they found important cases faster and found cases they might not have otherwise.

Advance testing of Westlaw Precision among 101 lawyers found that just 10 minutes into a research session, the lawyers had found three times as many relevant cases, TR says. Nearly all those lawyers said they found important cases faster and found cases they might not have otherwise.

Tackling Tedious and Imprecise Research

The problem TR sought to address with this new version of Westlaw is the difficulty of and time needed for legal research, Mike Dahn, head of product management, Westlaw, told reporters during a media briefing Monday, which was also attended by Paul Fischer, president, legal professionals, and Andy Martens, head of research products and editorial.

Customer surveys indicated that researching a complex legal issue typically takes a lawyer from 12 to 22 hours.

Dahn identified three reasons for this, and they are familiar to anyone who has done legal research: Searches often retrieve irrelevant cases, miss relevant cases, and return so many results that they can take hours to review.

Westlaw Precision tackles these shortcomings in legal research by performing an intricate operation of tagging the law, facts, outcomes, procedural posture and parties by topic “at new levels of specificity.”

While the tagging has been done by both humans and using machine learning, Dahn emphasized the human element as critical to the precision in Precision.

Over the last 18 months or so, TR added 250 attorneys to its editorial staff to perform this tagging. Dahn and other TR executives on the briefing emphasized that this project builds on the grand tradition of editorial review that has distinguished West since the company’s founding 150 years ago this year.

West’s editors organized the first “living taxonomy” of the law, said Paul Fisher during the briefing, and their efforts “are still foundational to the metadata and legal intelligence we offer today.”

Coverage is Limited

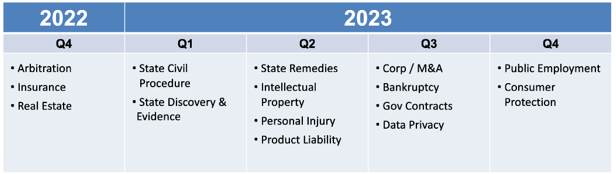

Reflecting the challenge of this massive tagging effort, coverage of Westlaw Precision is limited in the topics and cases it covers. As it launches today, it will be limited to:

- Eight topics: commercial law, federal civil procedure, federal discovery and evidence, federal remedies, federal class actions, employment, securities, and antitrust.

- Cases from the last 12 years, plus some older leading cases and U.S. Supreme Court cases.

- Published cases.

Before the end of the year, coverage will be extended to arbitration, insurance and real estate. Next year, coverage will be extended into the areas indicated by the chart below.

Customers who upgrade to Westlaw Precision will still have full access to all the content, features and functionality of Westlaw Edge, so they will still be able to research as they have previously done, but with the addition of these new capabilities.

Researching Using Precision

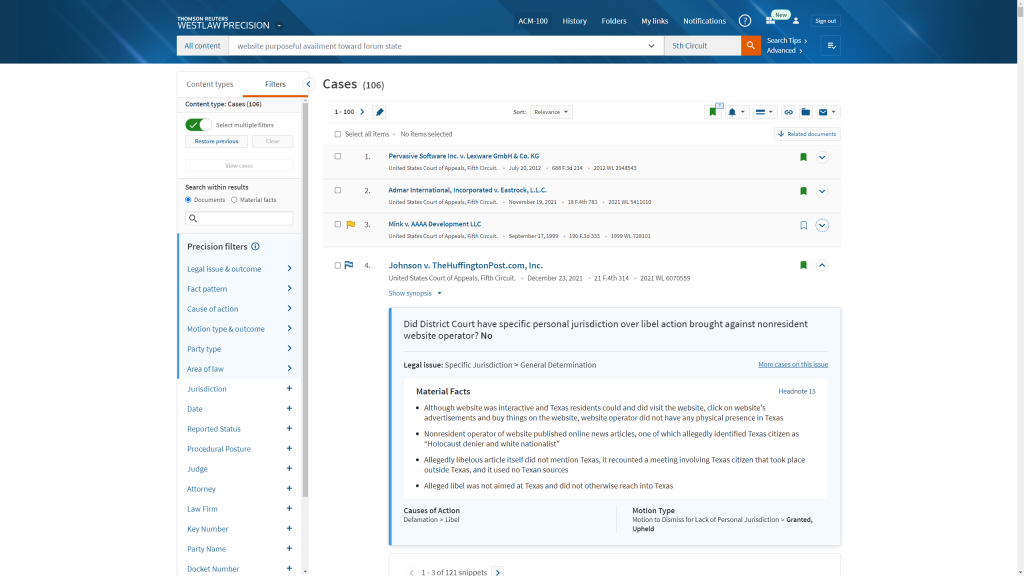

Westlaw Precision provides a new Precision Search feature by which users can search for specific attributes related to the legal issue and outcome, the fact pattern and material facts, the cause of action, motion type and outcome, party type, and area of law.

A user can also just run a search in the traditional method, and then apply Precision’s filters to zero in on results, or use a More Like This button when viewing a case to find other cases with the same legal issues or fact patterns.

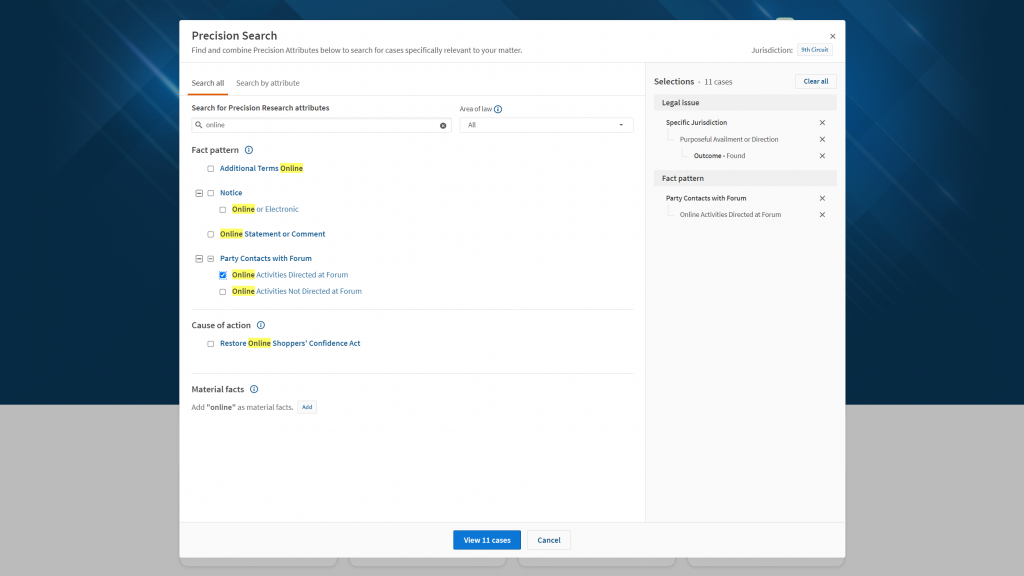

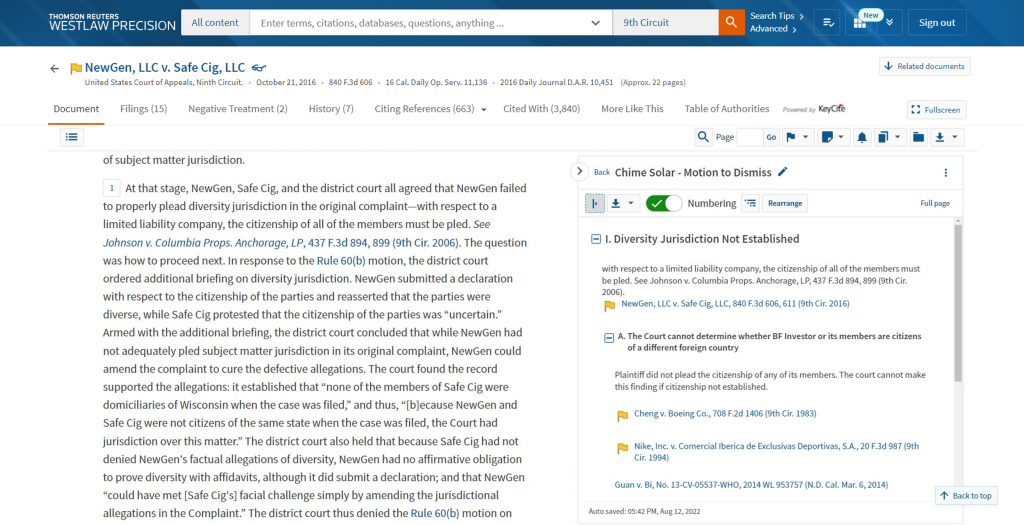

In the briefing, Dahn demonstrated with an example of a lawyer researching the question of whether service of process by email is sufficient on a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction.

The Precision Search template.

A traditional search using that query brought up 285 documents. Dahn said that it took a researcher three hours to review just the first 100 cases on the list, and that review found nine relevant cases. The researcher continued to seek more cases by using Key Number system and reviewing the headnotes those brought up, and then using KeyCite to find additional cases. All that took a total of 4.75 hours and found a total of 12 relevant cases.

Using Precision, the researcher would click Start Precision Search and then type “service of process.” That brings up a list of legal issues, of which one is “sufficiency of method.” The user selects that and then selects “sufficient” to further filter results by only cases where service was sufficient.

With a further search of the word “email,” the researcher finds the fact-pattern attribute for service of process that is specific to “social media or email service.” The researcher selects that and then searches for the motion to type, finding the attribute “motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction.”

So now the researcher has created a search that specifies the legal issue (service of process, sufficiency of method, outcome=sufficient), the fact pattern (service of process, social media or email service), and the motion type (motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction).

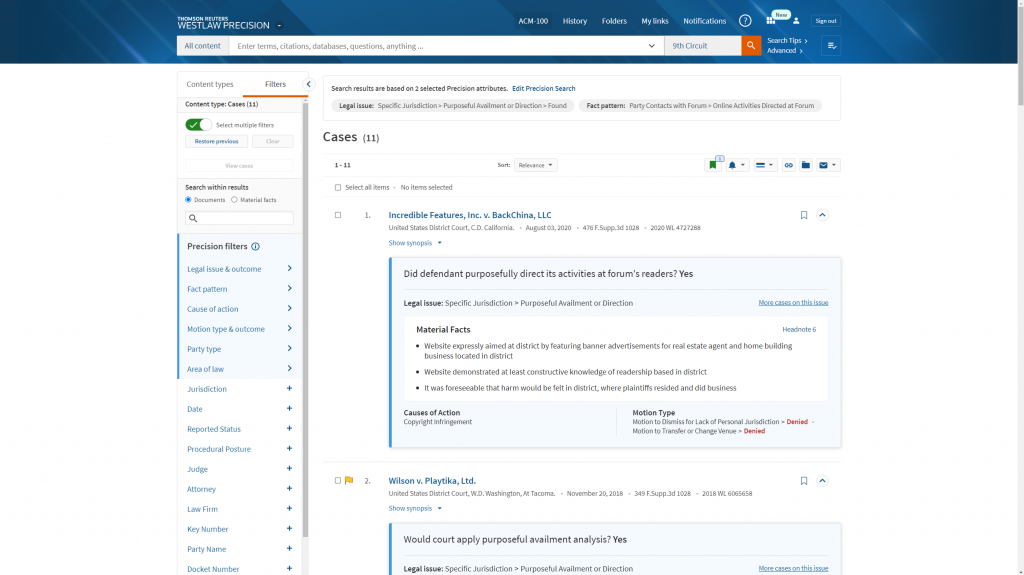

The results list from a Precision search.

That search, Dahn demonstrated, produces 10 cases, each with the right fact pattern, legal issue, outcome and motion type. Instead of reviewing 100-200 cases to find the 10 relevant cases, the researcher reviews just 10.

Another feature new in Precision is the Browse Box, which is designed to let a researcher move through results more quickly. Where before a researcher reviewing a case would skim through highlighted text related to the search query to decipher the case’s relevance, the Browse Box presents a statement of the issue decided in the case, how it was decided, the legal issues presented, and the material facts.

Having found the 10 cases, the researcher can then use KeyCite to find any other relevant cases.

According to Dahn, this Precision research session took 1.75 hours — three hours less than the 4.75 required by the traditional method.

Dahn said that TR tested Precision with a group of 101 attorneys who spent 1.5 hours doing research, half of them on Precision, the other half on Westlaw Edge. The Precision users were able to find in 20 minutes what it took the Edge users 45 minutes to find, he said.

When asked their subjective impression of Precision, 97% of the attorneys who used it said it helped them get to important cases faster and 90% said it helped them find cases they might not have found otherwise.

Other New Features of Precision

While this new approach to search is the most significant feature of Precision, it is not the only enhancement. Precision includes five other new features.

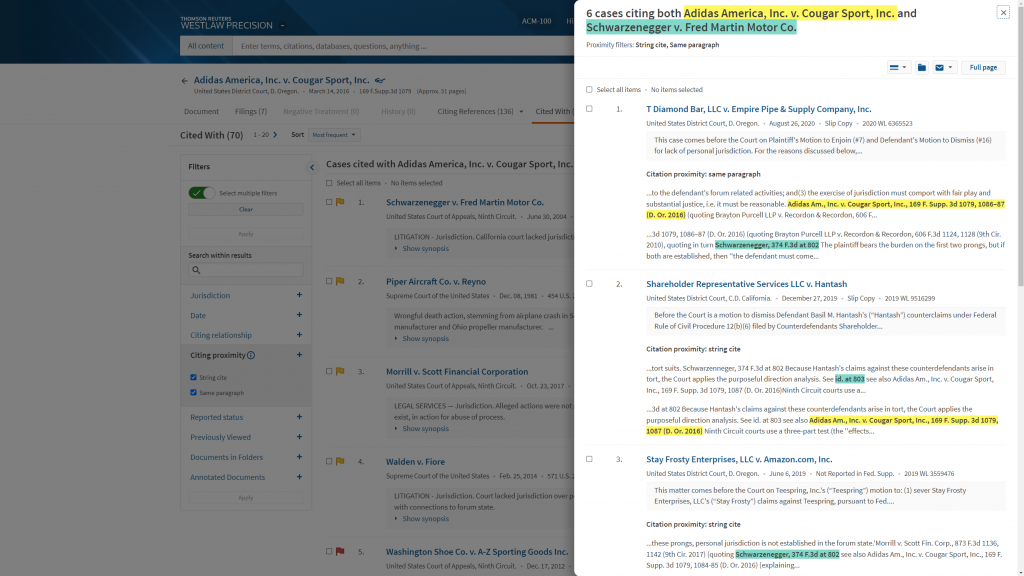

KeyCite Cited With

KeyCite Cited With. This new KeyCite feature shows related cases that have a pattern of being cited together even if neither cites the other. Whereas traditional KeyCite shows other cases that cite to the KeyCited case, KeyCite Cited With shows the cases that have been most often cited with that case. “They are highly likely to be relevant,” explained Dahn, “since they’re being cited with that case.”

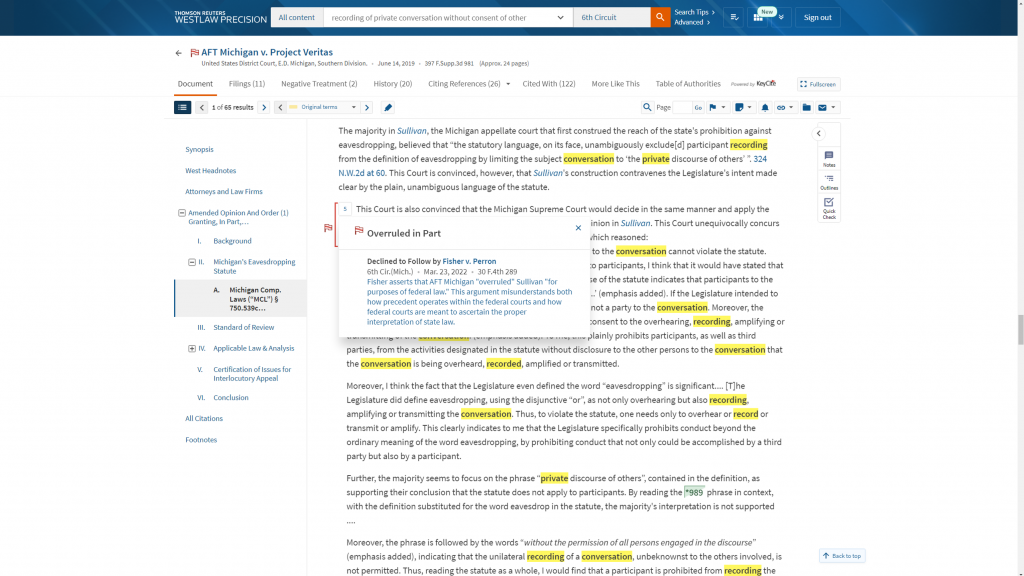

KeyCite Overruled In Part

KeyCite Overruled in Part. This feature add a new KeyCite flag — a red-striped flag — to indicate that a case has been overruled in part. It allows the researcher to navigate directly to the language in the case discussing the point of law that has been overruled. In the past, when KeyCite gave a case a red flag to indicate it no longer good law, it was often true that only a part of the case was no longer good, while other parts had not been overruled. It was up to the researcher to read the case and figure out which part was overruled. With this new feature, it identifies the specific parts of a case that are no longer good law.

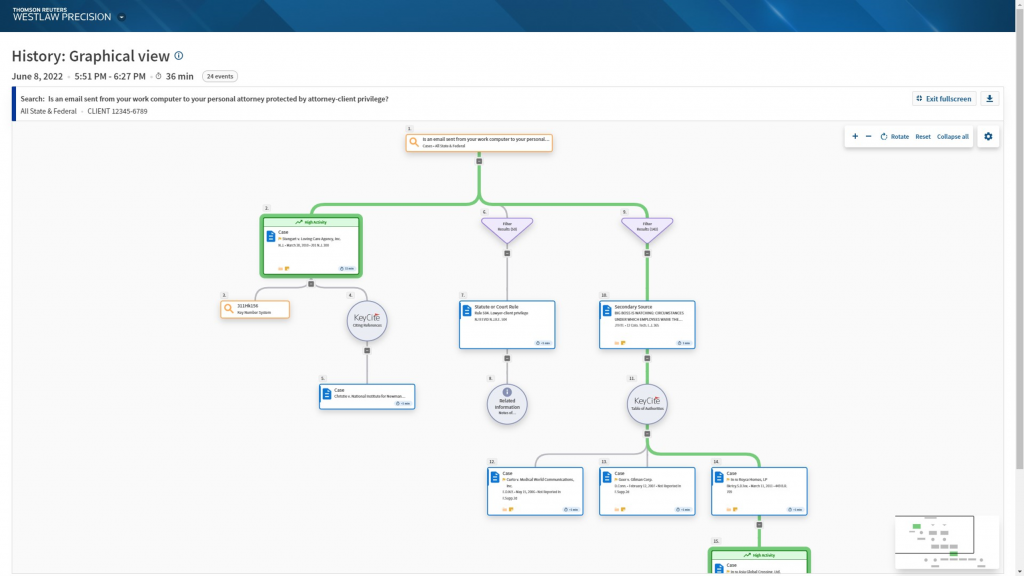

Graphical View of History

Graphical View of History. This feature displays a graphical visualization of the user’s research history, mapping out each step and highlighting the searches and documents on which the user spent more time.

Keep List/Hide Details

Keep List/Hide Details. This feature allows users, while reviewing search results, to save cases of interest and hide cases they have determined are not relevant to current research.

Outline Builder

Outline Builder. Designed to reduce the back-and-forth between Westlaw and Microsoft Word during a research session, this allows users to organize their research within the Precision browser window by dragging and dropping text into an outline. Citations are linked and formatted automatically, and the outline can be exported to Word to begin drafting a brief. Dahn said this may not be a big deal to users with multiple monitors and plenty of screen real estate, but for users working only on a laptop, it can save them the cumbersome need to switch back and forth between applications.

An Editorial Effort that will Fuel AI

Dahn and other TR executives on the call emphasized repeatedly that this product is the result of a massive editorial effort but also carries through all the machine learning and artificial intelligence developed in Westlaw Edge. Dahn said the development should be viewed as part of a continuum, with this massive tagging effort laying the foundation for the next wave of AI in Westlaw.

“Our testing demonstrated the value of Westlaw Precision, but we are just getting started,” Dahn said. “The editorial work we have done for more than a century has enabled us to do big things with artificial intelligence and machine learning in the last decade, and our additional investment in new editorial markup and classification lays the foundation for a new wave of innovation.”

Knowing that TR is a member of the SALI Alliance, which has developed a taxonomy of 10,000 tags for classifying legal matters, I asked Dahn if Precision is based on those SALI tags.

Listen: LawNext Podcast: Damien Riehl on the SALI Alliance and Setting Data Standards for the Legal Industry.

It is not, he said. He said that SALI’s classification scheme “is much less granular” than either TR’s Key Number system or its Precision research tool.

My Thoughts

This year marks the 150th anniversary of John West’s founding of his original publishing company that led to the formation of West Publishing and the development of the Key Number system that helped transform legal research.

Westlaw Precision feels like the Key Number system on steroids, classifying not just legal issues, but also other attributes that can help a researcher zero in on relevant cases.

It is, as Dahn acknowledged, a massive editorial effort, and therefore incomplete at launch. At a time when artificial intelligence technology is becoming so sophisticated at identifying relevant documents, one has to wonder whether this is the best and most sustainable approach to the future of legal research, or when, if ever, the tagging will ever be complete.

I wrote recently about a very different approach to delivering greater precision in legal research results: Casetext’s application of neural net technology. Westlaw’s and Casetext’s approaches to the future of legal research seem at polar opposites to each other, even acknowledging Westlaw’s sophisticated AI technology.

One carries on a tradition of recognized editorial excellence, but demands an army of editors and perhaps years to execute. The other relies on technology that cannot be fully explained, but that can be employed on a more nimble and agile basis. Does one or the other rule the future — or perhaps some hybrid of the two?

Or is, as Dahn suggested, all this editorial work simply laying the groundwork for a new wave of AI in legal research?

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog