On my left: the edge of the off-ramp, a modest guardrail, and a fifty-foot drop. On my right, inching closer: a tractor-trailer determined to occupy my lane. I hit the brakes. The truck kept rolling. Its wheels pressed into my car as it wedged me against the curb and carved a tail-to-nose dent in my poor Toyota.

This was early 2015, on my commute to Cambridge, Mass., the morning of a critical meeting at Harvard Law School, where I worked. Harvard professor Jonathan Zittrain and l were sitting down with Daniel Lewis and Nik Reed, the founders of a legal research startup named Ravel Law, along with lawyers from Harvard’s Office of General Counsel, Debevoise & Plimpton and Gundersen Dettmer. We’d all been working for over a year on a contract that would make it possible, someday in the future, for everyone to have free and open access to all the official court decisions ever published in the United States. After an exhausting year of negotiations, it was time to lock ourselves in a room and figure out if we had a deal.

| About the Author |

|---|

Adam Ziegler is a lawyer and software builder. He led the Caselaw Access Project and other work at Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab from 2014 to 2021. He works currently at TrueLaw, which helps law firms use AI to improve their operations and services. Adam Ziegler is a lawyer and software builder. He led the Caselaw Access Project and other work at Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab from 2014 to 2021. He works currently at TrueLaw, which helps law firms use AI to improve their operations and services. |

Fast forward nine years, and that “someday in the future” finally is here. On March 1, 2024, our collective efforts on this project — the Caselaw Access Project — culminated in the full, unrestricted release of nearly 7 million U.S. state and federal court decisions representing the bulk of our nation’s common law. I had the privilege to lead this work at Harvard for almost eight years. Wrecked Toyota aside, it was a career-defining experience, and I’m immensely grateful to everyone at Harvard and Ravel who worked hard to make it possible.

To mark the occasion, I wanted to share some of the project’s inside story, reflect on its impact and look ahead to what I hope this data will make possible in the future.

Why Even Do This Project?

Court decisions are public information — they’re authored by judges and issued publicly to tell us what the law is, and why. We all should have free, easy access to the law, and no one should gain competitive advantage from having privileged access to the law itself.

But historically we’ve not treated the law this way. Instead, we’ve acted like our law is created and owned by the companies that publish it. Our courts, with few exceptions, have allowed publishers to control access to the law and to dictate how we read, study, cite and use the law. Naturally, publishers have prioritized their commercial interests. They’ve made the law scarce and expensive. The effect has been to stifle innovation and competition in the field of legal information and, I would argue, to impede justice and the rule of law.

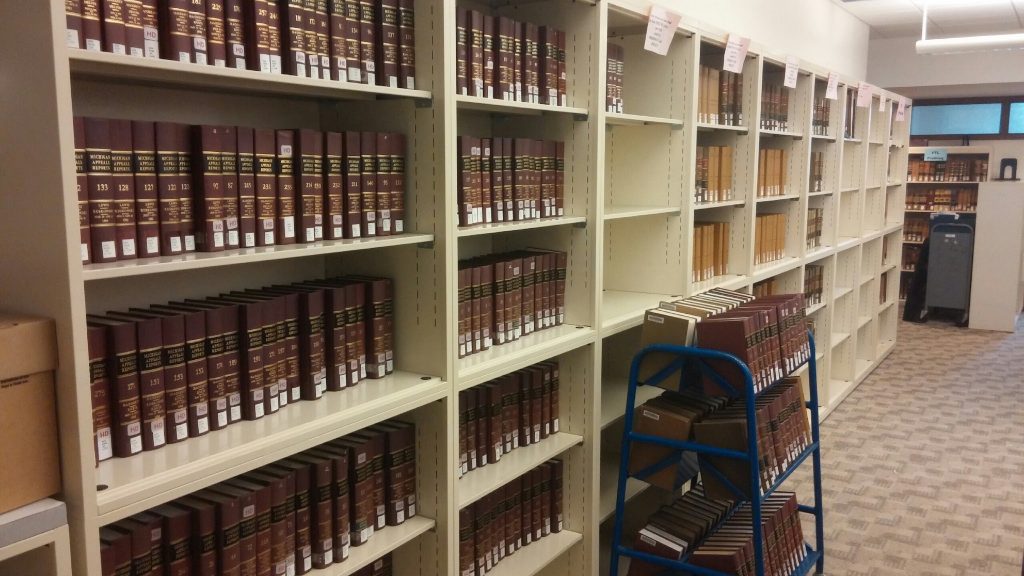

Harvard scanned 38.6 million pages from 39,796 books and converted it all into machine-readable text files.

This is why the Caselaw Access Project needed to happen and why it was worth doing, even with all the obstacles, frustrations and compromises along the way.

Let’s Make a Deal

I interviewed to join the Harvard Law Library and manage the project in late 2013, about a year after Nik, Daniel and Prof. Zittrain (or “JZ” as he’s affectionately known) had hatched the idea for the project and started working out a skeletal framework for a potential deal.

I’ll confess: when I first learned the project would not be paid for directly by Harvard, but instead would be funded by a venture-backed Silicon Valley startup that would get a few years of special access in return, I almost bailed. I thought it was absurd. Why would Harvard rely on a fledgling startup for this, especially at the cost of limiting access?

By the time we’d arranged ourselves around a conference table in early 2015, I had a different perspective. I’d spent the last year negotiating the deal with Daniel and Nik but also with Harvard’s many internal stakeholders. I’d come to understand that while Harvard’s librarians and resources made the project uniquely possible, Harvard’s bureaucracy and wealth also made the project virtually impossible. It was only through a capable partner like Ravel that the project had a real chance.

I’d also seen that Daniel, Nik and the Ravel team weren’t in it for purely commercial reasons. Although our team knew we had to give Ravel a few privileged years to exploit the project’s data, we drove a hard bargain to ensure the project would serve the interests of scholars and researchers and the broader public. Most importantly, we had to be certain that if (or when) one of the big publishers bought Ravel, their acquisition would not undermine the project’s goals. We had to make sure a buyer would be locked into continuing to support the project and would have no power to stop it. We were dealing with Ravel, but we were also negotiating against Ravel’s future buyer.

This led us to push for a battery of onerous protections and commitments. Ravel’s acceptance of these terms made clear to me that even within the context of their commercial goals, they shared the public interest motivations of the project. Most legal tech startups make bold declarations about public interest, access to justice and democratizing the law when it suits them. Very few make company-defining commitments that put those priorities front and center.

Ultimately, by mid-2015, the deal had taken shape. Harvard would contribute the law books and run the scanning process inside the law library. Ravel would pay for the scanning and subsequent data processing, including redaction of any extraneous material that didn’t originate from the courts. Both Harvard and Ravel would get access to the processed data. Harvard would have the right to share the data on a restricted basis immediately. Ravel would be obligated to provide public access from day one and would put its source code in escrow to secure this obligation. In exchange, Ravel would get an exclusive right to exploit the data commercially for roughly six years after we finished digitization – until March 2024. If Ravel or its successor ever stopped providing public access to the data, they would lose their commercial advantage and all the data would go free.

The contract still took a couple more months to finalize. There were other terms that were important to the investors and university administrators we needed to approve the deal. There were a few dicey moments where it looked like everything might fall apart over trivial concerns. But finally, we closed the deal and the signature pages hit my inbox. A short while later, we publicly announced the project and the key terms of the deal.

Then came the real work.

Making Mass Digitization Work Inside the Law Library

Inside the library, we’d been eagerly gearing up for the digitization effort. In parallel with the negotiations, we’d run a proof of concept that allowed us to figure out the process, equipment, systems and staffing we’d need to meet our quality standards. We’d carefully modeled out the costs and timing. We knew exactly how many pages per day we could scan, how much it would cost and what dials we could turn to alter cost or throughput if needed.

When the deal closed, we were ready to go. We’d already tackled many of the toughest challenges:

- We didn’t know precisely which books to scan. There was no definitive list of “all the books containing official court decisions.” So we did research and made one.

- We didn’t have all the books we needed. Like many law libraries, we had stopped buying some of the books that contained official court decisions. They were too expensive, and almost no one ever used them. So we went out and bought books to fill the few gaps.

- Most of the books weren’t physically in the library building. They were 30 minutes away in the Harvard Depository, where they were mixed in with about 10 million other books. So we figured out how to get the 40,000 books we needed and move them over to the library efficiently.

- We had almost no book-level metadata, but we needed to record key information about every book, such as when it was published and what jurisdiction(s) it covered. We also needed to make sure there were no missing or damaged pages. So we created a process to visually inspect every book and to manually record the necessary metadata.

- To scan the books at high speed, we needed first to free the pages from their binding. So we bought a machine we called the “Guillotine,” which sliced through the spine of the books with a crashing thud. (Yes, there were physical safety considerations). The Guillotine was so heavy we had to put it on a reinforced floor. It was so loud we had to suspend work around exam time.

- The high-speed scanner was an amazing machine, but it wasn’t perfect, and so we had to do quality control on the scans to make sure they met our standards. Over the course of the scanning effort, we visually inspected roughly 20 million scanned pages.

- After scanning, we had to preserve the books, just in case we needed to scan them again or someone needed to reboot democracy. So we used a vacuum-sealing machine designed for meat-packing to individually seal every book into a moisture-resistant bag before shipping them all to an underground limestone mine in Kentucky.

- We had to find space for all this in the library, where students studied, faculty worked and librarians served. We had to put the metadata stations, the Guillotine, the scanner, and the vacuum-sealer in separate areas, on various floors, which meant our team had to physically transport small carts full of books between stations on an elevator.

- And finally we had to keep track of all 40,000 books every step of the way, so we could account for each one, continuously monitor our progress and verify that we had processed every book we needed to. So we built custom software and adapted a hand-scanner system so we could check in every book at each station.

Overcoming these practical challenges was the hardest work we did, and the success of this phase was due entirely to the professionalism, dedication and adaptability of the library team in the face of quite a bit of pressure and skepticism, including from within Harvard. There were no high-paid consultants, distinguished thought-leaders or pompous muckety-mucks telling us how to do this. Mostly it was just a bunch of library professionals, a programmer and a token overbearing lawyer rolling up our sleeves in the basement and striving together to figure it out because we cared. Real innovation.

How Imperfect Law Becomes Imperfect Data

Scanning was the hardest thing, but it wasn’t the only thing. We also had to transform 40 million scanned page images into structured data representing all of the individual cases, which could be displayed for people on the web, downloaded in bulk and served machine-to-machine through APIs.

We had a lot of help here, both from Ravel and from the vendor we relied on to handle the processing. What stands out especially from this phase are two, related things: redaction and imperfection.

The Unfortunate Need to Redact

In the project’s early years, the remote possibility that a legal publisher might try to stop our work loomed large. It consumed a lot of time, energy and resources, and it forced us to make compromises.

The problem was this:

- Many of the books that contain our official case law were published by companies that had a history of acting aggressively through litigation to prevent others from copying the law or from competing in the realm of legal information.

- While no one would claim in good faith that court decisions authored by judges can be copyrighted by publishers, many publishers had adopted a practice of injecting into the text of judge-authored decisions a variety of editorial devices (such as headnotes and other annotations). In these, publishers did claim copyright.

- This intermingling of editorial content with official statements of law has a contaminating effect. You cannot get your hands on the official common law without also touching editorial content, which is harmless to read but somewhat radioactive to copy and share.

To achieve our goals on the project, we had to contend with this gnarly problem. The only solution available to us was redaction.

Redaction means the removal or obfuscation of unwanted information. “Unwanted” is exactly how we felt about the headnotes and other editorial materials embedded within the pages of the books we had scanned. We would have gladly worked with a “clean” version of the official law, but it did not exist. The only official version of the law was the contaminated one. And so we had to prioritize, above almost everything else, the accurate identification and removal of these unwanted materials from every page and every court decision that came out of every book that was not yet in the public domain. This was not easy.

The short version of this story is: we had to figure out what editorial content to expect in the scanned pages; we had to be ready to alert on any unexpected content; we had to identify where this content lived within a case and on a page; we had to excise this material from the textual data; and we had to paint solid black boxes over the content on the scanned images. We had to do all of this with extreme precision to ensure that everyone could see the law and no one could see the editorial litter.

Now let me tell you what I really think. Headnotes, key numbers, annotations and the like can be useful. Viewed in their own right, they’re not garbage at all. They’re the product of major investment and serious effort by trained professionals. There was a time when they were needed to assist the discovery and understanding of the law. They do deserve protection, but only as an independent enhancement layer that’s distinct from the law itself. When they’re combined with the official law in a way that interferes with propagation and access, they’re best viewed as pollution. It’s a great failure of our judges, courts and legislatures that they’ve allowed — and continue to allow to this day — commercial entities to mingle their owned commentary with our official law.

If you’re interested in learning more on this topic, I recommend reading the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org and the many briefs submitted supporting access to law, including the amicus brief that we filed. If you’re a redaction nut, please enjoy an example of our work on Vol. 323 of the Federal Reporter 2d.

Getting Comfortable with Imperfection

Because we invested so much in redaction, we had to make sacrifices elsewhere. The two biggest sacrifices were in the transcription of opinion text and in the scope of the project. We used a technology called optical character recognition (“OCR”) to extract all the case text from the scanned images. OCR output is not perfect. It typically requires some degree of machine and/or human correction. While we corrected some of the OCR output – text that identified parties and courts, for example – we did not correct the OCR output of the actual opinion text. In fact, the raw OCR quality is extremely good, and more than sufficient for most purposes. But it’s not perfect, and our law deserves perfection.

We also couldn’t keep digitizing the law forever. We had to limit the scope of the project, and we needed to turn our attention to the work of making the data accessible online. And so we had to end scanning in early 2017, although eventually we were able to extend it into 2018.

I’ve heard people question these compromises, as if they made the project pointless. That’s bunk. We calculated that if we made sure to create and share high quality scanned images and metadata for the full historical record — the work that would be hardest to reproduce — technology would continue to improve and others (ideally the courts) would step up to contribute going forward. Indeed, this is what’s happening. OCR technology is much improved, and it’s not too hard to redo the OCR to get better results. With all the images and metadata now freely, publicly available for anyone to access, we can all go to work making the text fidelity even better.

As for the project’s scope, Ed Walters and the good folks at Fastcase (now vLex) generously agreed to share their transcriptions of some newer court decisions. At the same time, the non-profit Free Law Project, led by Mike Lissner, continues to set the standard and do a far better job than the government itself in providing widespread public access to newly issued court decisions and case dockets. The courts haven’t done their part yet, but I’m still hopeful.

So the data isn’t perfect. It’s a little bit stale. But these gaps are closing, and someday they’ll be gone.

Access, Exploration and Experimentation

Everything I’ve shared to this point was a precursor to the ultimate end goal: free public access online. Ironically, when we started, we had no idea what public access would look like or if our team in the library would deliver it. This is why we made sure the contract required Ravel to deliver public access.

An Awkward Dance

Then in June 2017, LexisNexis announced that it had bought Ravel. Their public statements expressed an intention to continue supporting the project and to follow through on Ravel’s commitments. Privately they said the same thing. They had little choice; they inherited the contract, and it was airtight. Either follow through and gain the benefit of the remaining commercial exclusivity and a friendly relationship with Harvard, or renege and see all the data — which by this time was nearly complete — go free immediately.

But words are easy. In practical reality, we were caught in an awkward dance in which Lexis did the minimum required under the inherited agreement, and only if we held them to it. Their follow-through on public access was perfunctory at best. I would’ve been happy to see Lexis lean into the opportunity and become a bold standard-bearer for true public access to law. I also would’ve been happy to see Lexis wholly abandon the commitments Ravel had made. But now that the hard digitization work was basically done, I had little interest in frantically waving around the contract and chasing Lexis to do something it had no intrinsic motivation to do. I also knew it would be difficult and frustrating to get Harvard to throw any real institutional weight behind persuading Lexis to do much more.

So instead of focusing our energy on pushing Lexis, we started working earnestly within the Library Innovation Lab to take advantage of the rights the contract gave us to offer public access directly ourselves.

Delivering on Public Access

This was my favorite part of the project. This is what our Library Innovation Lab loved to do and did best: design and code high-performing, open source software that would fulfill the fundamental library mission of enabling access to knowledge.

We had almost free rein to build anything we wanted that would make it easier for people to read and study the law. The biggest question we faced was whether to try to build a free legal research tool that might substitute for expensive commercial products. We decided not to. Instead, we focused on providing direct access to the data. We wanted to enable others to build tools and products, and we wanted to explore new ways of interacting with the data. We did build a simple search and viewer interface for those who just wanted to read a few cases, but we chose mainly to prioritize things that commercial vendors would never do.

It’s hard in a post like this to describe the technology we built, so instead I’ll invite you to use the Caselaw Access Project and, if you’re so inclined, to copy and remix the project’s code. When you visit CAP today, you’ll see that the legacy site and tools are still available at https://old.case.law, but they’re set to sunset in September 2024 now that there are no restrictions on the data and everyone can do what only the Lab could do before. Check out Trends, an amazing interface built by the Lab’s current director, Jack Cushman, to allow people to explore how legal language and ideas evolved. Another favorite of mine is Colors, built by Anastasia Aizman in 2019 as an early, whimsical exploration of the data using natural language processing and neural networks.

The Virtues of Good Plumbing

These explorations mattered, but our biggest technical achievements were not the vivid demo applications we built ourselves. The real contribution was constructing the robust “plumbing” through which we could deliver the data to others.

The plumbing we built had two main parts: an API and a bulk data service. The technical details are amazing, and if technical details are your thing, stop reading and go look at the code. Reach out to Jack Cushman and the Lab’s current team to learn more about what we did. Find ways to contribute to the amazing work the Lab is doing now in the areas of legal AI and web archiving.

Broadly speaking, we designed the API for people writing computer programs that would need on-demand access to information about particular U.S. court decisions, or who wanted to maximize what they could do with their daily allotment of full-text cases. We designed the bulk data service for verified non-commercial researchers who wanted to work with large volumes of court decisions to gain some new insight or to investigate big ideas across the dataset.

One key emphasis was to slice and dice and repackage the data in as many ways as we could, to support the widest possible range of users and uses. As a result, now you can get PDFs of the scanned images, either as individual cases or whole volumes. You can get cases as JSON or XML, with the text of opinions as plaintext, HTML or XML. You can get whole cases, or just the metadata. You can get smaller datasets reflecting any of the time periods, jurisdictions, courts and titles in the collection. You can get specialized datasets that reflect all the citation-based connections (the “citation graph”) among cases. You also can create your own specialized datasets based on any search term and a variety of complex filters. If you want to quickly curate and download a dataset of all decisions issued between 1960 and 1990 by courts in Iowa, which mention “farm” and cite to the Indiana Supreme Court, go for it. If you want to put the entire collection of published U.S. court decisions on a thumb-drive, have at it.

Impact

While immersed in solving the practical challenges of the contract, the scanning, the processing and the delivery, we didn’t think much about the impact the project might have once we made the data available. We took it on faith that someone would find it useful.

We launched both the API and the bulk data service publicly in late 2018 and got a wave of favorable publicity. The one bit of recognition that stands out for me was an editorial in the The Harvard Crimson titled “In Favor of the Caselaw Access Project.” For some reason, there’s something special about a student publication expressing gratitude for our work.

Publicity is not the same as impact. What really mattered was whether people used the data. For a while it was hard to know what people were doing, but now we can start to see the evidence. If you look at references to the project on Google Scholar or SSRN, you’ll see hundreds of articles across a dizzying array of topics like antitrust law, linguistics, judicial partisanship, tax law, organ transplant litigation, machine learning and LLMs, legal pedagogy, and the long-term common law influence of cases involving enslaved people, just to name a few. If you search on the web, you’ll see over 50 library guides that highlight the project as a source for legal research or scholarly data and hundreds of thousands of links into the project’s website. If you look at Reddit, you’ll see an endless scroll of posts mentioning the project in all sorts of useful (and some wild) contexts. If you look at Github or HuggingFace, you’ll see a growing number of technical projects using and crediting the project. If you talk to lots of legal tech startups, like I do, you’ll hear how much easier it is to start something new because of the project.

This is only what’s public and easy to find in a few minutes online, or what people I happen to talk to are willing to share. This is just in the relatively short time since we launched the data, and all of it came during a period in which we had to artificially limit and condition access. Now the floodgates can open.

What Comes Next?

Now I shift from personal recollection and observation to speculation. What comes next as a result of the Caselaw Access Project? I don’t really know.

I believe the project will continue to enable scholarly research that helps us better see the harmful patterns, prejudices and past failures of our legal system, so that we can work together toward something much better. In law school, I learned a lot about civil procedure and commercial transactions but absolutely nothing about how our courts handled slavery before the Civil War. For a long time, I was ignorant about the active efforts of our profession in perpetuating this sin. But through the Caselaw Access Project’s data and tools, I learned that protecting slavery was one of our courts’ most prominent early priorities. Through important work by others using the data, I’ve learned that this shameful legacy continues to influence our law today.

I also have a strong hunch that generative AI will transform the legal industry, and that the project’s data will play a meaningful role. My hope is that the project will make it easy for smart, creative people to explore new AI-enabled ideas that would have been impossible if the law remained locked away in books and proprietary databases. I’m happy that it will be within reach for anyone with technical skills to build their own version of an AI legal assistant, rather than it being reserved only to companies with special access to the law. I also suspect the project’s data will be part of the solution to citation hallucination, and I hope courts will soon realize that the root causes of this problem are bad lawyering and inaccessible law, not technology.

There are positive versions of the future in which the project contributes to tools and services that help lower the access to justice barrier, improve the quality and value of legal work and allow people to better understand their rights and obligations. These are the future scenarios I’m committed to and will continue working toward enthusiastically.

But there are also versions of the future in which technical experts, with no awareness of or regard for the nature of the law, might use the project’s data to inadvertently do dangerous and harmful things. Here I’ll share a word of caution about the common law and the data we’ve helped make available: it’s always complicated, often ugly and frequently just plain evil. These cases are full of horrific details of violence and suffering. The people mentioned in the cases are real. Many of them, or their families and friends, are still living. And finally, over the course of the 350-plus years represented in the dataset, the law has often been horribly, disgustingly wrong. Don’t make the mistake of believing the law of Alabama or Massachusetts from 175 years ago is fit to inform a modern-day free legal advice chatbot. Don’t assume judges are always impartial or never prejudiced. Don’t presume all law is good law.

These are not reasons to keep the law closed or to continue giving privileged access to a few large companies, but they are compelling reasons for all of us to be thoughtful about how we use and share the data. Perhaps they are reasons, going forward, for judges to think differently about how they write opinions and what details need to be made explicit for a decision to carry its weight.

***

All in all, I’m incredibly fortunate that I could contribute to this project and work closely with so many amazing people to see it through from idea to impact. I’ve been lucky to work on a lot of great projects, but this one stands alone in every way. So worth it.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog