Citators — tools that validate whether a case or statute is still good law — have always been an essential component of a full-featured legal research platform. But in this age of AI-generated hallucinations, they may be more important than ever before.

Just two products have long dominated the legal research market as the gold standard of citators: Shepard’s from LexisNexis and and KeyCite from Westlaw. Bloomberg law also offers a citator called BCite.

Thus it was notable news this week when Paxton AI, a legal AI startup for contract review, document drafting and legal research, announced the launch of the Paxton AI Citator, which it says overcomes the failings and limitations of the established products.

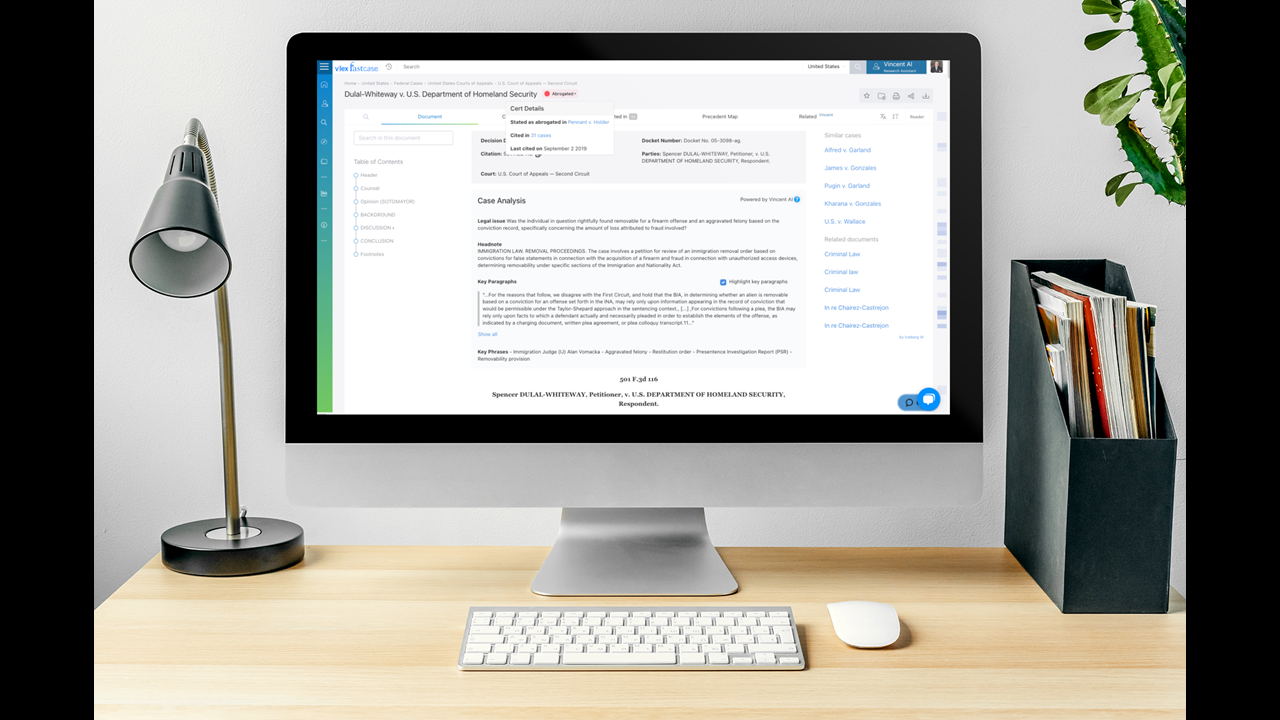

Less publicized but also of potentially major significance is the nationwide launch by vLex of its citator, called Cert, which it finished developing in May. It is being incorporated into the new vLex-Fastcase platform that the company is rolling out this year to bar associations, and has already rolled out in Florida and Louisiana.

Are Human Editors Needed?

Significantly, in their search for the holy grail of a reliable and accurate citator, Paxton and vLex have taken very different routes — and where those routes diverge is in the use of human editors.

Whereas the established citator products Shepard’s and KeyCite rely on human editors to update or verify the status of a case or statute, Paxton says it has been able to build a highly accurate citator without the need for human editors, by leveraging generative AI.

When it evaluated its citator against the Stanford Casehold dataset of 2,400 examples testing whether a case was overturned or upheld, Paxton says, its citator achieved a 94% accuracy rate.

The company has released a sample of cases that show how its citator performs along with an explanation of its assessment and a human-validated review of each case in the benchmark test set.

Paxton recently filed a patent application for its citator. It declined my request for a copy of the application, which is not yet available through the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office.

vLex Cert Uses Humans for Validation

By contrast, after spending many years and dollars developing its citator, vLex concluded that it was not possible to achieve a high degree of accuracy without employing human editors as part of the process.

The evolution of vLex’s Cert traces back to a Fastcase feature called Authority Check, which would let you see how a case had been cited. In 2013, Fastcase enhanced Authority Check with a feature it called Bad Law Bot, which would identify cases that had been reversed or overturned.

But Fastcase cofounder Ed Walters, now chief strategy officer at vLex since the merger of the two companies, said Bad Law Bot’s operation relied on harvesting citation signals in subsequent cases that identified a case as reversed or overturned. Where there were such signals, it was highly accurate, but if an overturned case was never subsequently cited, Bad Law Bot would not know that it had been overturned.

Thus, if Case A was overturned by Case B, Bad Law Bot would not know that unless and until some Case C cited Case A and noted it as reversed. But the vast majority of overturned cases never get cited by that Case C, Walters told me.

“So it was certainly better than nothing, and it picked up a bunch of treatments that Lexis missed, but it was not going to solve the citator problem,” Walters said.

“We always sort of said, ‘When we get big enough, when we get enough momentum behind us, we’re going to go find a way to crack this nut,” he said. “This is the holy grail.”

For Fastcase, one major step towards cracking that nut came in 2020, when it acquired the technology of Judicata, the innovative legal research platform for California law. Judicata had developed a citator that worked amazingly well, Walters said, but only for California cases, and Fastcase planned to launch it for the other 49 states and then the federal courts.

“I think it is fair to say we may have underestimated the difficulty of expanding that citator beyond California. Let me just say it directly: We underestimated the difficulty of expanding that citator beyond California.”

Fastcase was in the early stages of developing that Judicata citator technology for other states when it merged with vLex. The merger enabled that development to be accelerated, and, after two years of further development costing several million dollars, the work was completed in May.

While Cert uses AI up to a point, it also incorporates human editorial review. The reason for this is that vLex found that AI could tag the relationships between cases with a high degree of accuracy roughly 60% of the time. But 40% of the time, AI could not do it with a high-enough degree of confidence. For that 40%, vLex decided, there was no substitute for human editorial review.

As a result, vLex had a team of editors in Charlottesville, Va., spend two years reviewing more than 700,000 references one by one, and those editors will continue to review cases as part of the Cert product.

“I think there’s not a really good substitute for it — at least we were not able to identify a good substitute for it. I think Lexis and Westlaw would probably say the same thing.”

How vLex Cert Works

vLex Cert assigns cases to one of five classification types, with several specific classifications within each type:

vLex Cert assigns cases to one of five classification types, with several specific classifications within each type:

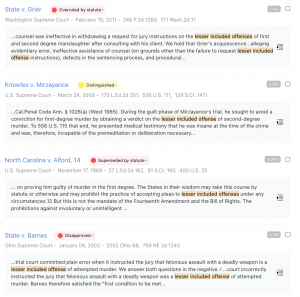

- Positive. These treatments appear in green and include those in which a subsequent case follows the cited case: Applied In, Affirmed In, Approved In, Followed In, and Relied Upon.

- Neutral. Where the subsequent case ascribes no value to the cited case: Cited In, Considered In, and Referred To.

- Caution. Where the subsequent case declined to apply the cited case: Distinguished In, Not Applied In, and Not Followed In.

- Negative. Where the subsequent case found that the cited case was no longer good law: Disapproved In, Overruled In, and Reversed In.

- Unclassified. Where the subsequent case has not been classified by vLex editors.

These treatments are displayed alongside the case name on both the search results page and within the case itself. To learn more about this, see these vLex support pages:

How the Paxton AI Citator Works

Paxton recently published a blog post that provides a detailed walk-through of how its citator works, Check that out for more details.

Paxton recently published a blog post that provides a detailed walk-through of how its citator works, Check that out for more details.

I have not used it, but based on that post, the citator would become available after a user asks a research question. In Paxton’s example, the user asks, “explain the evolution of abortion rights from the 1950s to the present.”

Like other generative AI research tools, Paxton synthesizes the relevant case law and provides an answer. If the user wants to know the status of any case that was used in providing the answer, the user would choose the “References” dropdown and the select, “Check case status.”

Paxton then begins to analyze the case. It says it reviews the case itself, every case that cites to the case, and cases that are semantically similar to the case.

Once Paxton’s analysis is complete, the user can navigate to the Paxton Citator tab to see an in-depth analysis of all “Important Cases” where Paxton highlights significant case relationships.

Paxton explains why it highlights each case as important. For example, Paxton says, if the user ran the citator on Roe v. Wade, Paxton would return Dobbs v. Women’s Health Organization as an important case, recognizing that Dobbs overturned Roe, stating that the relationship “can only be accurately categorized as ‘overturned.”

The Holy Grail?

Both for legal research companies and their customers, citators are critical tools.

“There are only a couple of legs of the stool that keep people subscribed to West or Lexis instead of Fastcase or vLex,” Walters told me. “And the citator was definitely one of the legs of the stool.”

Put another way, a viable citator is essential for a legal research company to be competitive in the market.

Generative AI, and its tendency to hallucinate, makes it even more essential to have a citator.

“With retrieval augmented generation in Vincent AI, you don’t want to answer questions based on overturned law,” Walters said. “Maybe that’s obvious, but without a citator, you could be creating research memos based on overturned law.”

Others have also tried to crack this nut, with mixed results. A decade ago, Casetext, long before it was acquired by Thomson Reuters, launched WeCite, a crowdsourced citator in which uses could add citation references and analysis to a case and other users could vote up or down on those references.

Later, Casetext developed a different citator, SmartCite. It tagged cases by using the signals used in subsequent citing cases. So if the judge in the subsequent case used contrary citation signals such as “but see,” “but cf.” and “contra,” SmartCite would tag the case with a yellow flag.

With their new citators, vLex and Paxton have taken different approaches to finding that holy grail. While both use AI, vLex takes it a step further, with “editors in the loop” to validate results.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog