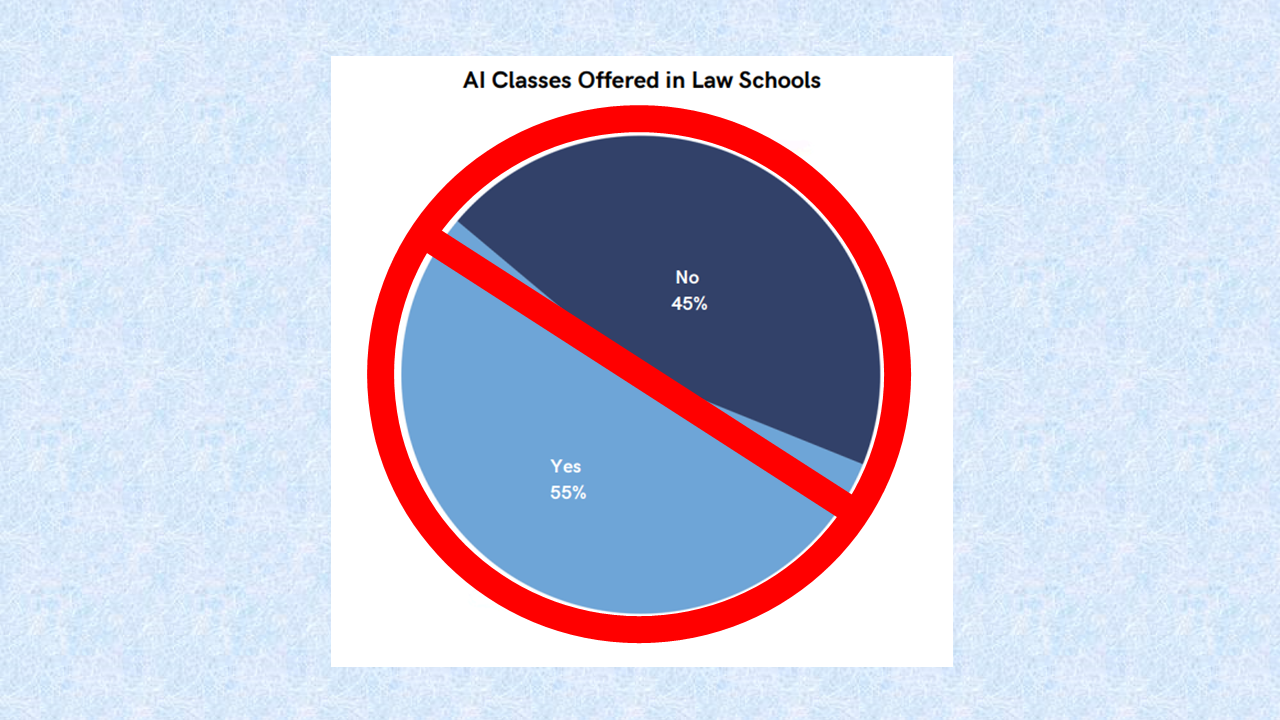

This recent Reuters story caught my attention: “More than half of law schools now offer classes on AI,” it said, citing a new survey conducted by the American Bar Association. Other reports in the news and on LinkedIn sounded a similar takeaway.

Indeed, the survey, AI and Legal Education Survey Results 2024, recently released by the ABA’s Task Force on Law and Artificial Intelligence, found that 55% of the law schools that responded to the survey now offer classes dedicated to teaching students about AI.

Even more, the survey said, “an overwhelming majority (83%) reported the availability of curricular opportunities, including clinics, where students can learn how to use AI tools effectively.”

But here’s the rub: According to the ABA, there are 197 accredited law schools in the United States. This survey said it was sent to 200 law school deans, so it must have included some unaccredited schools.

Of those 200 schools, just 29 replied.

So when the survey said that 55% of respondents now offer AI classes, it meant just 16 law schools.

Do the math: That is 8% of all law schools, not 55%.

And when it said that 83% reported the availability of AI-related curricular opportunities, that translates to 24 schools, or just 12% of all law schools.

To be fair, the authors explicitly state that the survey is “not a scientifically reliable measure of how legal education as a whole is responding to AI,” citing the limited sample size and potential response bias.

Still, the survey includes sweeping conclusions, such as this:

“Overall, the survey suggests that AI is already having a significant impact on legal education and is likely to result in additional changes in the years ahead. With a majority of responding law schools offering dedicated AI courses and providing opportunities for students to engage with AI tools, it is evident that legal education is evolving to meet the demands of a profession increasingly shaped by technological advancements.”

Among those who conducted the survey was Andrew Perlman, dean of Suffolk University Law School. I asked him, in light of the survey’s small response rate, what he thought was the import of the findings. Here is what he said:

“As noted in the report itself, the low response rate makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about what law schools are doing overall. For example, it’s certainly possible that law schools that are already doing more work in this area were more inclined to respond to the survey, making it seem as though a larger percentage of law schools are already adapting.

“That said, I think the survey can be read to mean that a material number of law schools are responding aggressively to developments related to AI in general and generative AI specifically. I view the survey results to be a sign of what is to come in terms of legal education, even if the survey may not be a valid measure of what’s currently going on at every school.”

Perlman’s more measured view seems the more accurate one. Undoubtedly, those law schools that now offer AI classes are harbingers of what is to come.

But do more than half of law schools now offer classes on AI? This survey simply does not answer that question.

My own scientifically unreliable guess: I highly doubt it.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog