When legal intelligence company vLex released a major upgrade to its Vincent AI last September, I wrote that it might just be the most capable generative AI assistant in the legal market. Now, vLex is releasing another major upgrade to Vincent AI that pushes it further beyond traditional legal research and document analysis, with distinct capabilities and coverage not available in other AI assistants.

The Vincent AI upgrade released today – which vLex is calling its Winter ’25 release – introduces multimodal AI capabilities for audio and video analysis, expands its jurisdictional coverage to 17 countries, and adds several new litigation-focused workflows powered by its Docket Alarm database of litigation data.

The company is also providing new details on its development of Vincent Studio, a builder space for law firms and legal departments to create their own workflow tools using Vincent AI’s technology and vLex’s legal data, combined with their own legal expertise. A beta version of the studio is now open, and those interested in testing it can request early access by emailing beta@vlex.com.

Analyze Audio and Video

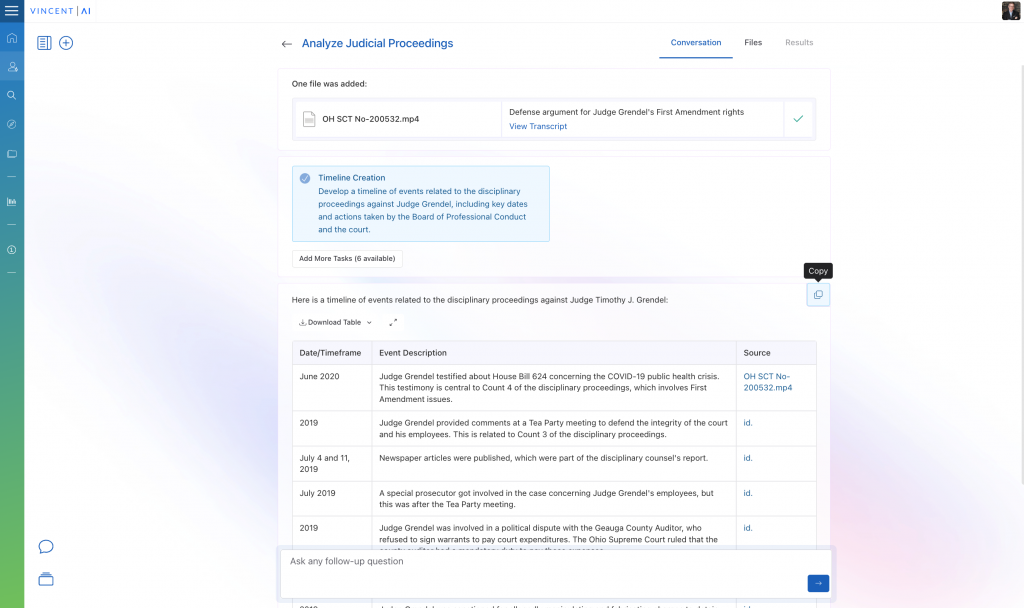

Of the enhancements and features announced today, perhaps the most unique is Vincent AI’s new ability to analyze audio and video files. It allows users to generate transcripts of recorded court proceedings, depositions, client interviews, and whatever else, and then perform legal analysis of the transcribed material and be prompted on suggested next-step legal tasks based on the content.

On Friday, I was given a demonstration of the new features by Ed Walters, chief strategy officer at vLex, and Alex Shaffer, Vincent AI’s product manager. They showed me how this new multimodal feature analyzed the video of an Ohio Supreme Court oral argument. It automatically generated a complete transcript and timeline of the proceedings, and then went on to identify key legal issues from the argument and provide links to related legal authorities, with the ability to click through to specific points in the transcript.

The Ohio case involved a matter of judicial discipline. After transcribing and analyzing the recording, Vincent AI suggested several workflow tasks specifically keyed to the content. For example, among the next steps it suggested were to explore the legal precedents regarding First Amendment protections for judges or to research the standards for judicial discipline in Ohio. The user can simply click on any of those suggestions to pursue that line of research.

While processing times for audio and video files will vary depending on the content, Shaffer said, most court recordings and audio files can be analyzed in 2-3 minutes. Some high-quality video files, such as the 1080p video from the Ohio Supreme Court, may take up to 8-10 minutes to process, he said.

Build An Argument

Today’s release also introduces an all-new “Build an Argument” workflow. Astute readers may recall that Vincent already had a feature called Build an Argument, which enabled users to find authorities for or against a stated argument. In fact, I wrote about it back in 2023, when vLex released the beta version of Vincent AI. But Vincent has now renamed that previous workflow Explore a Legal Proposition, and rolled out an all-new Build an Argument workflow.

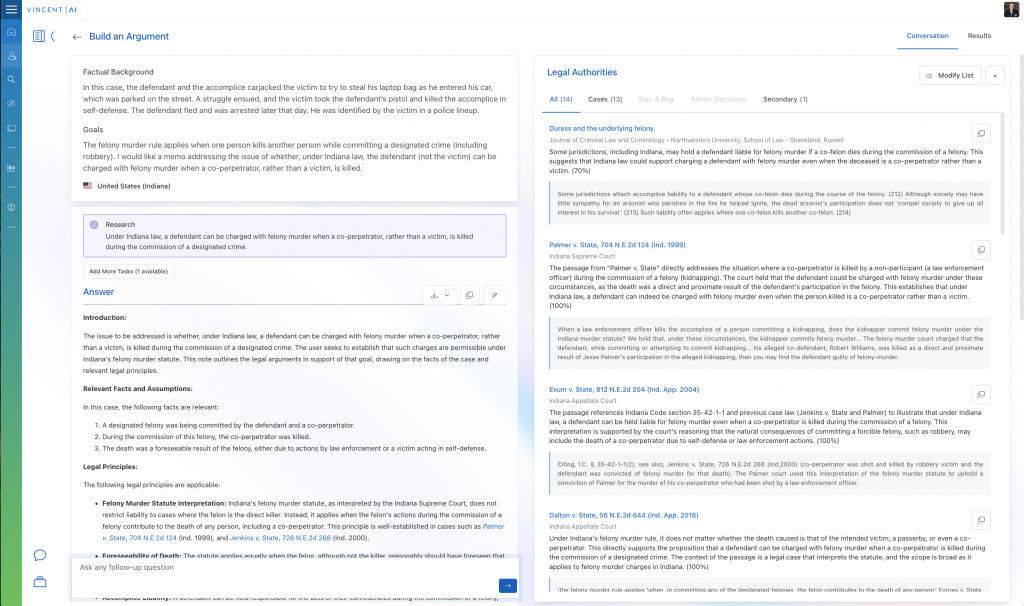

What this new workflow does is generate arguments based on the facts you provide as applied to the law. The user is able to enter narrative text describing the pertinent facts and then state a goal.

For example, in our demonstration, the user described a factual situation in which the victim of an attempted carjacking in Indiana grabbed the defendant’s pistol and shot his accomplice. The requested goal was to generate a memo addressing whether the defendant (not the victim) could be charged with felony murder in the death of his accomplice.

Vincent AI has a “prompt assist” feature that takes those inputs and suggests reworded research prompts, which the user is free to accept or reject. In this case, it suggested two, and the researcher selected this one: “Under Indiana law, a defendant can be charged with felony murder when a co-perpetrator, rather than a victim, is killed during the commission of a designated crime.”

Based on those inputs, Vincent will then generate the argument, with an introduction, legal analysis, and conclusion. It displays the argument in the left panel of the screen, with the supporting legal authorities shown on the right side of the screen.

“Vincent is actually going to perform ideation of a number of arguments that could support the user’s goal in light of those facts,” Shaffer said. “Then when it’s taking that research and analyzing the output, it’s going to actually apply the law to those facts.”

The factual background used in the demo is taken from a research exercise developed by the American Association of Law Libraries, and is one Walters has used in his own class at the University of Chicago Law School on generative AI in legal practice. Vincent quickly identified relevant precedent, including a seminal 1999 Indiana Supreme Court case that established key principles for felony murder charges when accomplices are killed during the commission of a crime.

“I’m pretty familiar with the question, and Vincent crushed the analysis here,” Walters said. “It identifies right away the seminal case from 1999.” He said his class has tested the same question in other AI legal research platforms and that Vincent “uniquely gets this right.”

In its response, Vincent also provides an “Areas of Risk” portion that points out exceptions to the rule or counterarguments. While a problem with some gen AI tools is their propensity to tell you only what you want to hear, Vincent is trained not to do that.

“The concern is that generative AI tells you what you want to hear, whether it’s true or not,” Walters said. “And we’ve really done this kind of work behind the scenes to make sure that Vincent is not like a sycophant.”

Litigation Analytics

While Vincent AI already offered several skills enabled by its integration with Docket Alarm and its database of over 850 million U.S. state and federal court records, today’s release introduces new Docket Alarm integration features that allow for sophisticated litigation analytics. These new workflows include:

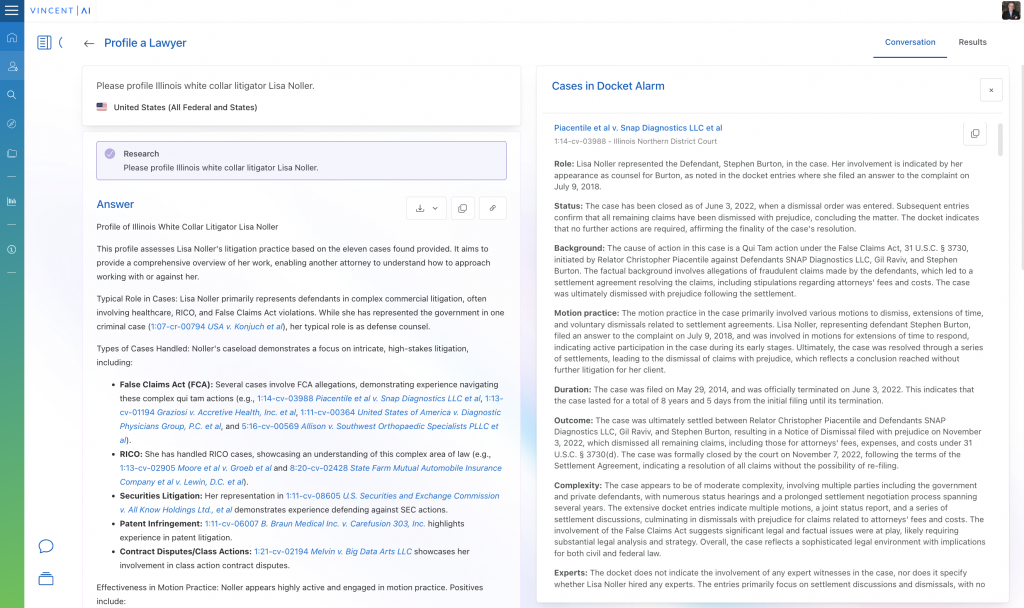

- Profile a Lawyer: Analyze motion success rates, typical roles in litigation, case duration trends, and notable cases.

- Profile a Law Firm: Review firm expertise, major clients, and practice strengths.

- Profile a Party: Examine settlement patterns, jurisdiction preferences, and outside counsel relationships.

- Profile a Judge: Get information on judicial preferences, reversal rates, decision patterns, and expert witness history.

- Docket Research: Conduct natural language searches across all Docket Alarm court records.

- Find Litigation Precedents: Uncover winning motions, briefs, and orders instantly.

In our demonstration, Walters asked Vincent AI to analyze how often summary judgment motions are granted in federal antitrust cases in the Southern District of New York.

Vincent then produced an analysis of a sample of 70 federal antitrust cases to provide a memorandum providing detailed insights about motion practice patterns, showing, for example, that such motions were ubiquitous, filed in the vast majority of cases, but saw varied outcomes. While Vincent shows the memorandum on the left of the screen, it shows representative cases on the right.

I asked Walters and Shaffer how Vincent’s docket analysis would compare to more traditional docket analytics products such as Docket Alarm itself or Lex Machina from LexisNexis. It is not an apples-to-apples comparison, they said, because the analytics in those other tools are dependent on tagging of the data, whereas Vincent’s language models enable it to answer open-ended questions regardless of tagging.

With Vincent, that means, a user could ask a question such as, “How often do data privacy cases involve children?” Even though there is no “child” or “children” tag in Docket Alarm, Vincent is able to perform this level of nuanced analysis.

Vincent’s integration with Docket Alarm also enables it to generate comprehensive profiles of attorneys and law firms, analyzing their litigation history, case outcomes, and practice patterns across the database’s 850 million court records.

In our demonstration, Walters asked it to research a specific white-collar litigator in Illinois. It produced what appeared to be a detailed profile, showing the types of cases the litigator most often handled and major clients she had represented, and even producing detailed overviews of the specific cases she had appeared in.

In another example, they asked it to analyze how noted lawyer David Boies responds to motions to dismiss in the Southern District of New York. Again, it provided a detailed response, accompanied by overviews of specific cases.

Expanded Country Coverage

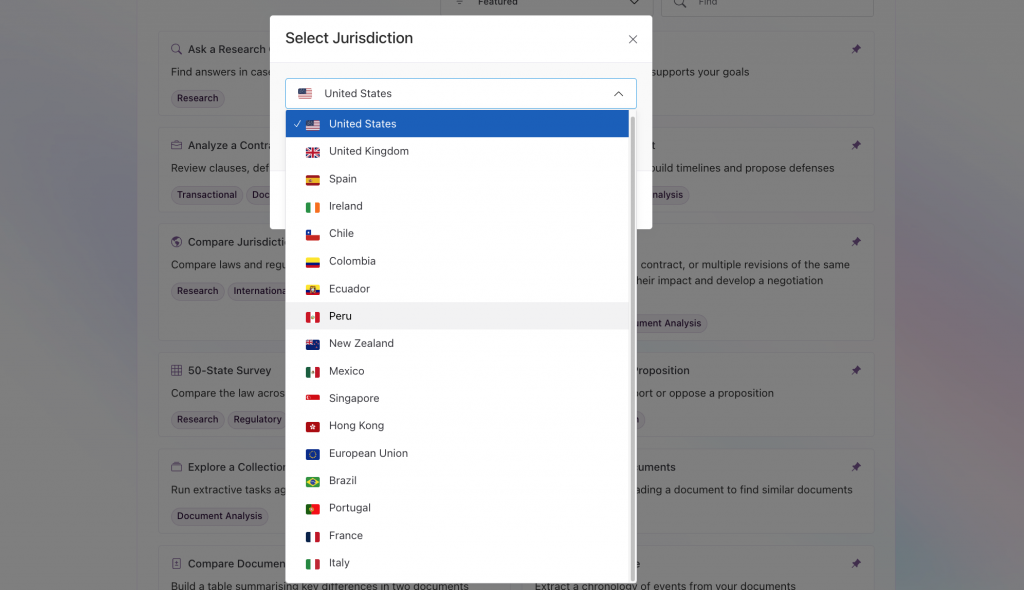

Today’s release also expands Vincent AI’s international coverage, adding four new jurisdictions – Hong Kong, Italy, Peru and Ecuador. These follow the addition of France, Portugal and Brazil last autumn and brings the total coverage to 17 jurisdictions.

Other jurisdictions covered are the United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, the European Union, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, New Zealand, and Singapore.

Although not specific to today’s release, Walters said that vLex continues to prioritize security and data privacy. The platform recently completed SOC2 certification in addition to its existing ISO 27001 compliance, and operates with zero-retention agreements with its language model providers. This is particularly important for features like client intake interview analysis, where sensitive information may be processed, Walters said.

Vincent Studio

With regard to Vincent Studio, which is now in beta, Walters and Shaffer said it will allow law firms to create their own custom workflows, using the Vincent AI technology and vLex database of legal and docket resources.

“The idea with Studio is that we’re working towards a graphical user interface, no-code environment where users can apply their own data sets and prompting and utilize the tools that we’ve already added to Vincent to create solutions to their firm’s own unique problems,” Shaffer said.

Firms can apply to participate in the beta by emailing the company at beta@vlex.com. Shaffer said they cannot guarantee they will be able to offer access to everyone that applies, but they will look at every request and see if they can match it with scheduling and availability.

According to vLex, Vincent AI is currently used by eight of the 10 largest global law firms, along with Fortune 100 companies, governments, law schools, and law libraries worldwide.

With these new features that are part of the Winter ’25 release, Walters said he believes vLex is “adding to our lead” in developing gen AI tools for legal professionals.

“There are a lot of people who are building in this space,” he said. “Our aspiration is to be the best of all of them.”

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog