Over the weekend, OpenAI released Deep Research, an AI agent capable of completing multi-step research tasks and synthesizing large amounts of online information. OpenAI’s chief product officer Kevin Weil said it can complete complex research tasks in minutes that might take a person many hours or days, according to The New York Times, adding that it should be particularly useful for people in fields such as finance, science and law.

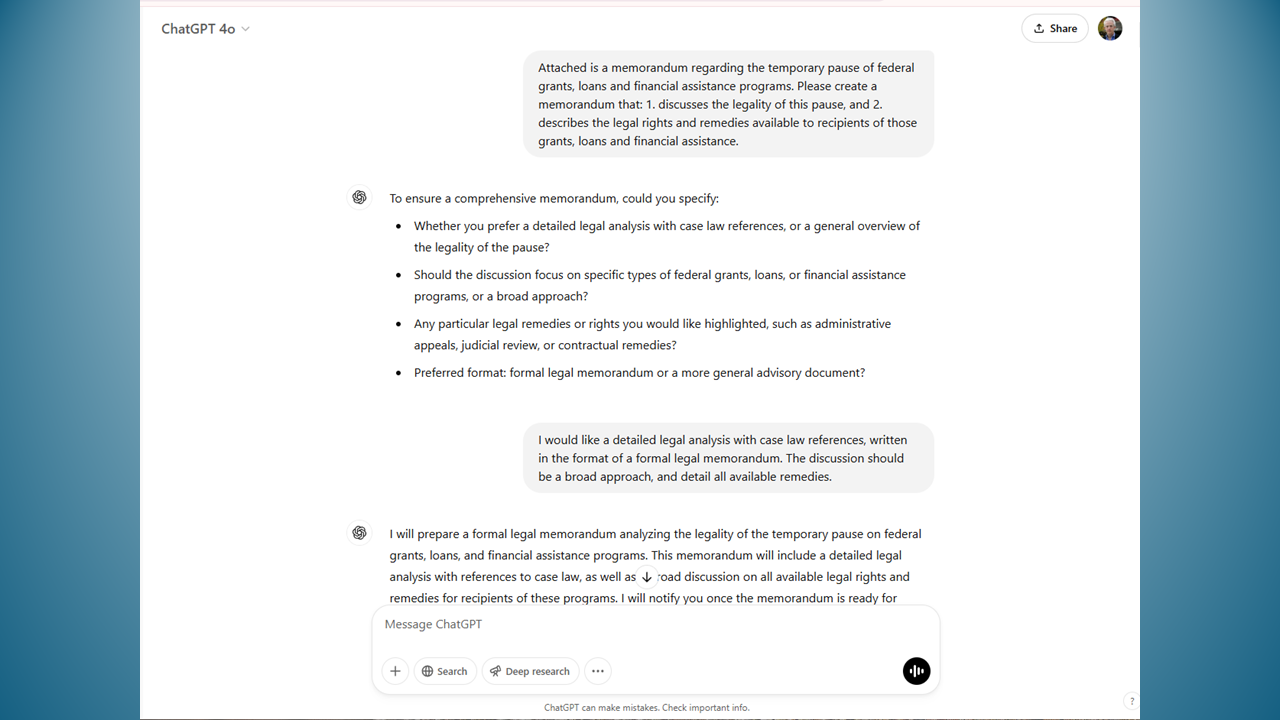

Curious to see what it can do, I have been running it through several research tasks today. In search of a meaty legal issue, I decided to ask it to research and analyze the legality of the Trump administration’s temporary pause of federal grant and financial assistance programs, and then to outline the potential legal remedies available to recipients of those grants and financial assistance.

In 10 minutes, it produced the following memorandum, which consumes 9,000 words and 17 single-spaced pages in a Word document, and which covers in some detail:

- Legal authority for the pause.

- Potential legal challenges.

- Relevant case law and precedent on agency authority to suspend or cancel aid.

- Legal rights and remedies of affected funding recipients.

- Arguments for and against the legality of the pause.

- Conclusion.

For the record, the memorandum ultimately concludes that the pause on grants and assistance “appears to rest on shaky legal ground.”

Note that it uses only publicly available sources, not paywalled legal research platforms. It typically cited FindLaw for cases and seemed to rely heavily on JD Supra for analysis. Query what it could have done with access to Westlaw or Lexis.

I am no expert in this area of law, and so I cannot assess the overall quality of the legal analysis and conclusions. But I think any lawyer would agree that this has the potential to be an even-more powerful AI tool than anything we have seen so far.

Read it for yourself (and let me know what you think).

To: General Counsel, [Agency Name]

From: [Your Name], Counsel

Date: February 3, 2025

Re: Legality of OMB’s Temporary Pause on Federal Grants and Financial Assistance (OMB Memo M-25-13) (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA)

Issue: You have asked for an analysis of the legal authority and challenges related to the Office of Management and Budget’s Memorandum M-25-13 (Jan. 27, 2025) imposing a temporary pause on federal grant, loan, and other financial assistance programs. This memorandum examines the legal basis for the pause, potential legal challenges (including conflicts with statutes, administrative law, and due process), relevant case law on agency suspension of funding programs, the rights and remedies of grant/assistance recipients, and arguments for and against the pause’s legality.

Facts and Background: OMB Memorandum M-25-13, issued January 27, 2025, directed executive agencies to “temporarily pause all activities related to obligation or disbursement of all Federal financial assistance” (to the extent permitted by law) while the new administration reviews these programs (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Agencies were instructed to halt new awards, stop disbursing funds under existing awards, and even consider modifying or “cancel[ling] awards already awarded” that conflict with the administration’s priorities (again, where lawful) (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) The memo’s purpose was to ensure federal assistance aligns with President Trump’s policies as outlined in several January 20, 2025 executive orders (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Certain programs were excluded from the pause, such as direct payments to individuals and mandatory spending like Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and SNAP (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) The pause took effect January 28, 2025 at 5:00 PM (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Although OMB formally rescinded Memo M-25-13 on January 29, 2025, after legal challenges, the White House indicated that the underlying funding “freeze” pursuant to the President’s orders remained in effect (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) Multiple lawsuits have been filed by nonprofits, businesses, and state attorneys general challenging the pause (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) and a federal court issued a temporary stay on January 28 to block the pause as it applied to disbursement of funds under existing awards (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra)

Legal Authority for the Pause – Constitutional, Statutory, Regulatory, and Executive Order Authority.

- Constitutional Framework (Spending Power vs. Executive Power): The U.S. Constitution vests the spending power in Congress. Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 (the Appropriations Clause) mandates that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law”, placing control of federal funds with Congress ( Appropriations Clause | U.S. Constitution Annotated | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute) This clause was intended “as a restriction upon the disbursing authority of the Executive” ( Appropriations Clause | U.S. Constitution Annotated | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute) In other words, the Executive cannot spend without an appropriation, and when Congress directs that funds be spent on specific purposes, the Executive must carry out the law ( Appropriations Clause | U.S. Constitution Annotated | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute) At the same time, the President has a constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” (Article II, Section 3). Past administrations have argued that this duty, along with the President’s executive powers, gives some discretion to manage or even delay expenditures to ensure efficient execution of the law or to accommodate broader statutory mandates (for example, avoiding waste or addressing emergency contingencies) (Impounding Appropriated Funds | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress) (Impounding Appropriated Funds | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress) However, the Supreme Court has never squarely recognized an inherent presidential power to refuse to spend appropriated funds. To the contrary, early precedent suggests the President cannot forbid execution of a law requiring expenditure: in Kendall v. U.S. ex rel. Stokes, 37 U.S. 524 (1838), the Court held that the President could not prevent a cabinet officer from disbursing congressionally mandated payments, emphasizing that the Take Care Clause does not imbue the President with power to ignore a precise legislative command to pay funds (Impounding Appropriated Funds | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress) Thus, constitutionally, the Executive’s authority to pause spending is at best limited and must be grounded in some lawful discretion conferred by statute – otherwise it risks contravening Congress’s power of the purse.

- Statutory Authority and Limitations: No statute expressly authorizes a blanket pause of all federal financial assistance programs for policy review. On the contrary, several statutes constrain the Executive’s ability to withhold or defer appropriated funds. The Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (ICA) was enacted in response to President Nixon’s impoundments and curtails executive refusals to spend appropriated money ( A Primer on the Impoundment Control Act | Lawfare ) ( A Primer on the Impoundment Control Act | Lawfare ) Under the ICA, the President may propose to “rescind” (cancel) funds, but the rescission must be approved by Congress within 45 days or else the funds must be released (2 U.S.C. §§ 683–684). The President may also “defer” (temporarily delay) spending in limited circumstances, such as to provide for contingencies or achieve savings through operational changes, but even deferrals must be reported to Congress and are subject to override (2 U.S.C. § 684, incorporating requirements now codified at 31 U.S.C. § 1512) (31 USC 1512: Apportionment and reserves) (31 USC 1512: Apportionment and reserves) The Antideficiency Act, 31 U.S.C. § 1512, similarly permits establishing reserves (withholding appropriated funds from obligation) only for bona fide contingencies or efficiency savings, or as specifically provided by law (31 USC 1512: Apportionment and reserves) Any such reserves must be reported to Congress under the ICA (31 USC 1512: Apportionment and reserves) In short, current law “often catches the executive branch in a vise: Presidents can neither spend money without an appropriation nor refuse to spend funds once Congress has provided them” ( A Primer on the Impoundment Control Act | Lawfare ) Given these constraints, a broad pause on expenditures must be rooted in some statutory discretion within the programs themselves or in general budget execution laws.

- Specific Program Authority: Many grant and loan programs are authorized by statutes that give the administering agency a degree of discretion in timing or conditions of awards. For example, some appropriations are “not to exceed” a certain amount, or to remain available for multiple years, which might imply that not all funds must be obligated immediately. Agencies might argue that unless a statute imposes a deadline or mandatory formula for distribution, a short-term pause is “permissible under applicable law” (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) to ensure funds are spent consistent with new policy directives. OMB M-25-13 explicitly instructs agencies to continue “legally mandated actions or deadlines” despite the pause (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) implying that where a statute requires funds to be distributed by a certain time or in a certain amount, agencies should comply. Additionally, OMB can rely on its ordinary budget execution authority to apportion funds in stages (e.g. quarterly apportionments) to prevent inefficient or premature spending, as long as this authority is not abused for policy impoundment. OMB’s general authority arises from the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 (31 U.S.C. § 1513) and the role of OMB in managing agency budgets. The memo cites the pause being “to the extent permissible by law” (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) reflecting these statutory guardrails. There is no known statute or appropriation rider that directly authorizes halting all grant/assistance outlays for a policy review; thus, the legal basis must be inferred from the combination of (a) agency discretion under program statutes to sequence or defer awards, and (b) the President’s general administrative authority over executive agencies.

- Executive Orders and OMB Guidance: President Trump’s executive orders issued on January 20–24, 2025 provided the policy impetus for the pause (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) For example, executive orders on “Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs,” “Enforcing the Hyde Amendment,” and others signaled that certain uses of federal funds were to be curtailed (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) The OMB memo was an implementation tool “to implement these orders” by reviewing and realigning programs accordingly (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) An Executive Order itself can direct agency heads to review programs or even pause specific activities, but it cannot override statutory directives. Here, instead of an express Executive Order commanding a spending freeze, the OMB (under the Acting OMB Director) issued the directive. OMB’s authority to issue such management memos comes from the President’s delegation of budgetary coordination functions. Often, new administrations have temporarily halted regulatory actions or pending grants via White House memorandum (for instance, previous transitions had brief moratoria on grants or contracts for review (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) . The key is that any such directive must operate within the bounds of existing law – OMB itself acknowledged nothing in the memo should be construed to affect legal entitlements like Medicare or Social Security (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB)

In summary, the Administration’s ostensible legal authority for the pause rests on the President’s constitutional role in executing laws and managing the executive branch, coupled with any flexibility in program statutes and the budget execution process. However, this authority is counterbalanced by clear statutory limits (the ICA and related laws) that prohibit unapproved impoundment of funds appropriated by Congress. If the pause is deemed to exceed those bounds – for example, by deferring mandatory spending without congressional notice, or by effectively cancelling funds Congress intended to be spent – it would lack legal authority.

- Potential Legal Challenges – Conflicts with Statutes, Administrative Law Principles, and Due Process. The OMB’s funding pause raises several legal issues that invite challenge:

- Conflict with Statutory Mandates / Separation of Powers: The foremost challenge is that a broad spending freeze violates Congress’s directives in appropriation and program statutes. Congress appropriated funds for these grant and assistance programs (many on an annual basis for FY2025) and often specified their purpose, eligible recipients, or timelines. A blanket pause could be characterized as an “impoundment” – an unlawful withholding of funds that thwarts legislative will (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) Courts have held that when Congress enacts a funding program, the executive must execute it consistent with the statute. In Train v. City of New York, 420 U.S. 35 (1975), for example, President Nixon directed the EPA to allot less funding than Congress had authorized for a water pollution control grant program. The Supreme Court found the statute “does not permit” the Executive to reduce allotments below the full amount Congress specified, rejecting the attempt to withhold funds (TRAIN v. CITY OF NEW YORK, 420 U.S. 35 (1975) | FindLaw) (TRAIN v. CITY OF NEW YORK, 420 U.S. 35 (1975) | FindLaw) Similarly, in City of Los Angeles v. Adams, 556 F.2d 40 (D.C. Cir. 1977), the court required the Department of Transportation to release withheld airport development grants, holding that absent a clear congressional authorization, agencies cannot simply refuse to expend available funds for their intended purpose. These precedents underscore that an across-the-board pause risks contradicting the “shall…disburse” language often found in program laws. Furthermore, if OMB’s pause extends the availability of funds beyond what Congress provided (for instance, causing annual funds to lapse without use), it squarely conflicts with the ICA’s prohibition on unreported deferrals. In short, plaintiffs argue the pause usurps Congress’s power of the purse by effectively amending appropriations acts via executive fiat (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) State plaintiffs also raise federalism concerns, as many grants fund state programs; a sudden halt might violate cooperative federalism statutes or impose new conditions not authorized by Congress (implicating the Spending Clause). The administration’s defense is that the pause is temporary and conditional – it does not ultimately cancel funds, but delays them for legitimate review. They stress the memo’s caveat “to the extent permissible by law” (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) and the allowance for legally required funding to continue (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Nonetheless, any significant delay in mandated funding can be painted as ultra vires. Notably, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) – which polices appropriation law compliance – would likely scrutinize whether this pause constitutes an illegal impoundment. (In a recent analogous situation, GAO examined President Biden’s 2021 pause on border wall funds and concluded it did not violate the ICA because the funds were eventually obligated consistent with the appropriation’s time frame (Department of Homeland Security—Border Barrier Construction and Obligations | U.S. GAO) (Department of Homeland Security—Border Barrier Construction and Obligations | U.S. GAO) The legality may turn on duration and intent: a brief, good-faith delay for administrative transition may pass muster, whereas an indefinite or policy-driven freeze would not.)

- Administrative Procedure Act (APA) – Arbitrary/Capricious Action and Procedural Violations: The APA provides a cause of action to challenge final agency actions that are arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or not in accordance with law (5 U.S.C. § 706). Here, the OMB memo (and agencies’ implementation of it) could be viewed as a final agency action setting a new policy of withholding funds. Affected parties argue the freeze is arbitrary and capricious because it fails to consider the reliance interests of grant recipients or the statutory objectives of the programs being halted. Agencies abruptly changed course on funding with essentially no reasoned explanation other than a broad change in administration priorities. There was no individualized review at the time of halting; the freeze applied across many programs indiscriminately, which could be seen as failing the APA’s requirement of rational decision-making. Additionally, the APA requires notice-and-comment rulemaking for new substantive rules or policy statements that significantly affect regulated parties, unless an exception applies. Arguably, a general pause on disbursements—especially directives to “withdraw… published [funding] announcements” and effectively amend grant terms (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) could be deemed a substantive rule or at least a significant policy change. No APA notice/comment process was followed; the policy was imposed immediately by memorandum. The administration would contend this was an internal management directive, not a formal rule, and that exigencies of a new administration constitute “good cause” to forego advance notice. Nevertheless, courts have shown skepticism when agencies attempt sweeping changes without procedural compliance. In the parallel context of regulatory freezes, courts have invalidated delays of duly issued regulations for failure to undertake notice and comment (see Clean Air Council v. Pruitt, 862 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2017)). The pause in grants could face a similar APA procedural challenge if viewed as effectively suspending or revising binding program rules.

Moreover, some plaintiffs assert that the OMB memo exceeds OMB’s statutory authority under the APA’s “not in accordance with law” and “in excess of authority” standards (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) OMB’s role is to manage budgets, but OMB itself does not administer grant programs; plaintiffs argue OMB cannot dictate program outcomes contrary to statutes or beyond any authority Congress has given the President or OMB. This overlaps with the impoundment argument – essentially framing the freeze as not authorized by any statute and thus “not in accordance with law.”

- Due Process Concerns: The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause may be invoked by recipients of federal grants or loans who claim a property interest in continued receipt of promised funds. The strength of this claim depends on whether the recipients have a legitimate entitlement to the funds. For new or yet-unawarded funds, applicants generally have no property interest in a mere expectation of a grant. However, for existing grants and agreements, especially where a grant award document has been executed and the recipient is entitled to draw funds for approved costs, there is a stronger argument that those funds are a form of property. Courts have held that certain government benefits, once conferred, cannot be taken away without due process (e.g., entitlements like welfare benefits required a hearing in Goldberg v. Kelly). A federal grant is not an entitlement in the same way by statute, but once an award is made, agency regulations often treat it as a binding commitment for the project period, subject only to limited grounds for termination (such as non-compliance by the grantee). Here, the OMB memo even contemplates canceling already-awarded grants that conflict with the new priorities, “to the extent permissible by law” (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) If an agency seeks to terminate or revoke an existing award, due process would require at least notice to the grantee of the reasons and some opportunity to respond or pursue an administrative appeal. A sudden, unilateral suspension of payments under an ongoing grant may be challenged as a deprivation of property without due process, especially if the grant terms or regulations did not contemplate such a pause for policy reasons. The administrative stay issued by the D.C. federal court reflects this concern – it specifically blocked the pause as to “disbursement of federal funds under all open awards,” thus preserving the status quo for existing grants to prevent irreparable harm (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) The court recognized that cutting off committed funding could immediately harm programs and beneficiaries, suggesting that such action likely triggers legal scrutiny. In defense, the government might argue that no protected property interest is at stake because the pause is temporary and the government has broad authority to suspend performance of its grant agreements pursuant to overarching federal law (and the grant’s terms usually incorporate compliance with all federal laws and executive orders). They might also point to 2 C.F.R. § 200.340, a regulation permitting termination of federal awards if they no longer effectuate program goals or agency priorities “to the extent authorized by law” (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) – implying that the possibility of termination for changed priorities is an understood condition of the grants. However, that regulation cannot override constitutional due process; if a grant is to be terminated, the agency must follow the procedures in its own regulations (which often require advance notice of termination and an opportunity for the grantee to object or cure deficiencies). Any deviation could be struck down as arbitrary or as a violation of required process (Accardi doctrine, which mandates agencies follow their own rules).

- Other Potential Constitutional Claims: The lawsuits also allege the pause violates the First Amendment and other constitutional provisions (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) The First Amendment theory likely arises from the memo’s explicit targeting of funding for “DEI [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion], woke gender ideology, and [the] green new deal” among others (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Plaintiffs argue this constitutes viewpoint-based discrimination in funding, penalizing organizations or programs that express or embody certain viewpoints (e.g., support for transgender rights or climate initiatives). If a grant program is being halted or grants canceled because of the content or viewpoint of the funded activity, that raises First Amendment issues (courts have held that while the government can choose what to fund, it cannot impose conditions that suppress constitutionally protected viewpoints unrelated to the purpose of the program). The administration will counter that it is simply refocusing on what it views as the proper policy goals, which it is allowed to do when those goals are germane to the program (for instance, not funding programs it deems ineffective or outside the scope authorized by Congress). This area of law (unconstitutional conditions and viewpoint discrimination in funding) is complex, and it would depend on the specifics of each program. Additionally, state attorneys general have hinted at Tenth Amendment or Spending Clause claims, essentially arguing the federal executive cannot unilaterally alter the bargain of federal-state grant programs or create coercive effects on states by withholding expected funds without Congress. While these arguments are more novel, they contribute to the overall claim that the pause is unlawful.

- Relevant Case Law and Precedent on Agency Authority to Suspend or Cancel Aid: Courts have addressed executive agency attempts to suspend, delay, or cancel financial assistance programs in various contexts. Key precedents include:

- Impoundment and Spending Cases: As discussed, Train v. City of New York (U.S. 1975) is a landmark case affirming that when Congress authorizes and appropriates funds up to a certain level for grants, the Executive cannot intentionally spend less in pursuit of its own policy preferences (TRAIN v. CITY OF NEW YORK, 420 U.S. 35 (1975) | FindLaw) (TRAIN v. CITY OF NEW YORK, 420 U.S. 35 (1975) | FindLaw) United States v. Kendall (1838) stands for the principle that the President cannot direct subordinates to ignore a congressional payment directive (Impounding Appropriated Funds | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress) City of Los Angeles v. Adams (D.C. Cir. 1977) and related D.C. Circuit cases from the 1970s (e.g., National Association of Regional Councils v. Costle, 564 F.2d 583 (D.C. Cir. 1977)) enforced that agencies must obligate grant funds to the extent Congress has made budget authority available, absent a valid reason grounded in law to withhold funds. More recently, in the context of Biden’s pause on oil and gas leasing (which is not a grant program but similarly an administrative pause of a congressionally established program), courts found the pause likely violated the statutory scheme. In Louisiana v. Biden, 543 F. Supp. 3d 388 (W.D. La. 2021), a district court enjoined the Biden Administration’s moratorium on new oil and gas leases, holding that the Mineral Leasing Act and Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act required regular lease sales and did not authorize a blanket pause; the court viewed the pause as contrary to law and arbitrary under the APA. This illustrates that courts look skeptically at agency actions that unilaterally suspend programs mandated or anticipated by statute. By analogy, to defend the grants pause, the government would need to point to some statutory flexibility to justify it.

- APA and Grants/Contract Cases: When agencies have tried to terminate or not renew grants for policy reasons, courts have intervened on APA grounds. A notable example is the series of cases involving the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPPP) in 2018. After a change in administration, HHS shortened the project period of previously approved TPPP grants from five years to three, effectively ending funding two years early with no explanation. In Policy & Research, LLC v. HHS, 313 F. Supp. 3d 62 (D.D.C. 2018), then-District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson held that HHS’s unexplained termination of the grants violated the agency’s own regulations and was arbitrary and capricious (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) She noted that agency decisions not to continue funding are typically “presumptively unreviewable” as committed to agency discretion, unless there are regulations or statutory guidelines that constrain the agency’s discretion (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) In that case, HHS had regulations on grant termination that limited its power (e.g., requiring certain findings or procedures), and the court found HHS failed to follow those rules, rendering the action unlawful (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) Other courts, including in the Ninth Circuit, likewise granted relief to the TPPP grantees (e.g., Planned Parenthood of Greater Wash. & N. Idaho v. HHS, 946 F.3d 1100 (9th Cir. 2020), which affirmed an injunction against HHS’s improper termination of grant funding). These cases set a precedent that grant recipients can challenge premature termination or suspension of funds when the agency deviates from governing legal standards or fails to provide a reasoned basis. Similarly, in Texas Neighborhood Services v. HHS, 875 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 2017), a nonprofit grantee challenged HHS’s disallowance of certain grant costs and termination of a Head Start grant. The D.C. Circuit entertained the APA claim (indicating such disputes are justiciable) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) The upshot is that while agencies have discretion in managing grants, that discretion is not boundless—courts will enforce compliance with any legal constraints (statutory or regulatory) and require rational decision-making.

- Contract Law Principles: In some cases, federal grants or loans may give rise to contractual obligations enforceable in court. For instance, federal loan guarantee programs involve contracts between the government and lenders or borrowers. If the government breaches such contracts by unilaterally suspending performance (e.g., not disbursing loan funds or grant payments when due), the aggrieved party could sue for relief. The Tucker Act (28 U.S.C. § 1491) allows contract claims for money damages in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. However, many federal grants are structured as assistance agreements rather than procurement contracts, and agencies often assert that grant agreements are not traditional contracts enforceable under the Contract Disputes Act. Nonetheless, courts have sometimes found an implied contract or used estoppel theories if the government’s actions egregiously undermine commitments. The OMB memo does contemplate cancellations “to the extent permissible by law,” which implies agencies should not breach legal obligations. If a particular grant agreement includes a clause allowing termination for convenience or change in government policy, the agency might invoke that (though such clauses in assistance awards are not common outside of specific program rules). Absent that, a grantee whose award is revoked might argue the government breached an agreement. Case law in this area is sparse, as most challenges are brought under the APA or program-specific review provisions rather than as straight contract suits.

- Equitable and Mandamus Relief: In extreme cases, courts have issued mandamus or injunctive relief to compel officials to release funds when a clear duty exists. For example, in In re Aiken County, 725 F.3d 255 (D.C. Cir. 2013), the D.C. Circuit granted mandamus ordering the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to resume processing a license application using appropriated funds, after the agency had halted the project (Yucca Mountain) contrary to congressional appropriation. The court stressed that executive agencies cannot simply ignore statutory commands due to policy disagreements, especially when Congress appropriates money for a specific purpose. While not a grant program case, it reinforces the principle that the judiciary can order officials to carry out the law as written.

- Legal Rights and Remedies of Affected Funding Recipients: Entities expecting or receiving federal grants, loans, or assistance have several avenues to seek relief if they are harmed by the pause:

- Administrative Remedies and Appeals: Many federal agencies provide administrative processes for grantees to challenge adverse decisions. For instance, if an agency suspends or terminates a grant award, the agency’s regulations (often mirroring the Uniform Guidance in 2 C.F.R. Part 200) typically allow the recipient to appeal or at least to engage with the agency. Some agencies convene an internal appeals board or an Administrative Law Judge to adjudicate grant disputes. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services utilizes the Departmental Appeals Board for certain grant terminations, and the Department of Education has an appeals process for resolving audit findings and terminations. In the context of the OMB pause, a recipient whose specific award is canceled or suspended might first seek clarification or reversal from the agency’s grant officer. The OMB memo itself allowed OMB to grant exceptions on a case-by-case basis (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) so one practical step is to request an exception if the pause is causing severe harm and no law actually permits delay for that program. However, because the pause was a centralized directive, administrative relief at the agency level could be limited unless and until OMB lifts the pause (which, in fact, it formally did by rescinding M-25-13 (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) though the freeze continued informally). Importantly, if an agency does terminate an award, due process (as noted) would entitle the grantee to notice and an explanation, and possibly a chance to object or provide information on why the termination is unlawful. Exhausting such administrative remedies can strengthen a later court case, but in an emergency (like funds being imminently withheld), many plaintiffs have proceeded directly to court for injunctive relief, as seen on January 28, 2025 (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra)

- Judicial Review (APA Lawsuits): The primary legal remedy is to file suit in federal court under the Administrative Procedure Act or relevant program statutes. The APA allows any person aggrieved by final agency action to seek judicial review unless the action is committed to agency discretion by law. Here, recipients (and organizations representing them) have sued OMB and agencies, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief to set aside the OMB pause as unlawful (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) They requested Temporary Restraining Orders, which were partly granted (administrative stay) to block the freeze on existing awards (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) In such suits, plaintiffs can argue the legal points discussed (statutory violation, APA violation, constitutional claims). The court can provide a remedy by enjoining the enforcement of the pause (stopping the agencies from withholding funds) and by vacating the OMB memorandum if it’s found to be an illegal rule or policy. Judicial review is also available under specific grant program statutes in some cases – for example, if a statute provides for judicial appeal of agency decisions (certain education and highway programs have such provisions). However, APA is the broad catch-all. If successful, plaintiffs might secure a preliminary injunction (short-term relief) and ultimately a permanent injunction or order compelling agencies to resume normal fund distribution. Courts have expedited these cases given the time-sensitive nature of funding (as evidenced by the hearing schedule in the nonprofit case (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) . Notably, the APA does not allow monetary damages, but only equitable relief. If funds were wrongfully withheld and the fiscal year lapsed, a court could potentially order the agency to use other available funds or request re-appropriation, but that scenario is complex – hence the emphasis on timely injunctive relief.

- Contractual Remedies (Claims for Breach): If a particular grant or loan is clearly contractual and the government’s pause constitutes a breach, the recipient could file a claim with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims under the Tucker Act. For example, a university with a cooperative agreement might argue that the agreement is an enforceable contract and that the government’s failure to pay out committed funding is a breach. The remedy would be expectation damages (the unpaid amounts). However, the government would raise defenses such as sovereign immunity (claiming the agreement is a grant, not a procurement contract), or cite provisions that allow suspension of performance due to government orders. Grants often incorporate by reference federal regulations that include termination clauses, which could complicate a pure breach claim. In practice, few grant recipients pursue direct damages claims because of these uncertainties and because maintaining the relationship (getting the grant back on track) is usually preferable to litigation that could take years. Loans and loan guarantees are a bit different: if the government simply refuses to honor a loan disbursement without justification, the borrower or lender might have a straightforward breach claim (since loan agreements are contracts). They could also sue for specific performance (to compel the loan) or an injunction. Another “contractual” angle is the Federal Grants and Cooperative Agreements Act, which distinguishes procurement contracts from grants. Federal courts generally treat grant disputes as administrative/APA matters rather than contract disputes, unless there is a clear contractual undertaking.

- Legislative Recourse: Recipients can also turn to Congress for relief. Since Congress holds the purse strings, it can exercise oversight or pass legislation to countermand the pause. Already, members of Congress have objected strenuously, calling the pause an unlawful impoundment (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) Congress could utilize hearings, subpoena agency officials, or request GAO investigations to pressure the administration. GAO’s legal opinions, while not court judgments, carry weight – a GAO finding that OMB violated the ICA would reinforce challenges and could prompt a political response. In terms of direct remedies, Congress could enact a rider clarifying that funds “shall be obligated without delay” for certain programs, or even a specific statute mandating continuation of grant distributions notwithstanding any executive order or memorandum. In extreme cases, if funds expire due to the pause, an aggrieved recipient could lobby Congress for a private relief bill or an appropriation extension to restore the lost funding. Additionally, the Congressional Review Act (CRA) theoretically allows Congress to disapprove a major rule from the executive – if the pause memo were considered a “rule,” Congress might attempt a resolution of disapproval (though the CRA process is typically for regulations and requires presidential signature or veto override, making it impractical here). Ultimately, the threat of congressional action can be a remedy in itself: in this scenario, OMB rescinded the memo within two days (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) likely due to both legal and political pressures.

- Contractual and Equitable Relief via Grant Terms: One often overlooked avenue is the terms of the grant agreements themselves. Some grant awards may include dispute resolution procedures or provide that the agency can terminate the award “for convenience” or if in the “public interest.” If an agency invokes such a clause to cancel a grant, the recipient can invoke whatever remedy the grant terms allow (sometimes the right to claim reimbursement of certain costs, or the right to a written explanation). If no such clause exists, the recipient can argue the agency had no contractual right to terminate early. Equity comes into play if a project is abruptly defunded – a court in equity could order the agency to temporarily continue funding to avoid immediate harm (akin to a preliminary injunction) while the dispute is resolved. Though rare, courts have issued orders to continue funding pending proper termination procedures (as in the TPPP cases, where HHS ultimately had to process continuation awards for the grantees after the courts ruled the terminations invalid).

In summary, affected recipients are not without recourse: they can seek internal agency relief, but more effectively they can sue under the APA for an injunction and rally congressional oversight. The swift legal action and partial court-ordered stay in this instance show that these remedies can indeed halt or reverse an improper pause (at least with respect to critical funding flows) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra)

- Arguments For and Against the Legality of the Pause:

- Administration’s Defense of the Pause: The administration will advance several arguments to defend the legality of the funding pause:

- Broad Executive Management Authority: Upon a presidential transition, the President is entitled to redirect executive agencies to better achieve the law’s purposes consistent with new policies. The pause is portrayed as a prudent management step, within the President’s Article II powers, to ensure “faithful execution” of the law in light of new executive orders. They will cite that past Presidents (including immediately after inaugurations) have issued temporary freezes on certain funds or regulations for review, which were generally accepted as part of executive oversight (often termed “regulatory freezes” or spending holds pending policy review). The memo itself recites that career and political appointees have a duty to align spending with the President’s priorities (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) implying that this is a legitimate exercise of executive direction.

- Statutory Compliance (“Permissible by law” carve-out): OMB deliberately included language that the pause must be carried out only as far as the law allows (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) The administration argues this savings clause protects any actions that must happen under statute – those will continue. Agencies were even instructed to identify any “legally mandated” funding actions during the pause and report them (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) and to continue required obligations or administrative steps by law (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) Therefore, they contend, no law is actually being broken – if a statute unequivocally requires a grant by a deadline, the agency will meet it (or seek an exemption from OMB). For all other funding, where timing is discretionary, the President can lawfully delay for a short period. This frames the pause as consistent with the ICA: a temporary programmatic delay, not an intent to cancel funds. (The administration could cite GAO’s determination that pauses “to the extent permitted by law” – like Biden’s border wall pause – did not violate the ICA as long as funds were eventually prudently obligated (Department of Homeland Security—Border Barrier Construction and Obligations | U.S. GAO) )

- Temporary and Reversible Nature: The pause is expressly temporary – agencies had to report by Feb. 10, 2025 with information, and OMB would then issue guidance on moving forward (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) The memo was in effect only a short time before being formally rescinded on Jan. 29. Even if the freeze continues under the radar, the administration can argue that this is not an indefinite withholding (which would be a clear impoundment) but a brief review period. Courts sometimes allow short delays for administrative convenience or transition, distinguishing them from permanent policy cancellations. The defense would emphasize that no final decision has been made to cancel any program; as such, any challenge might be deemed unripe or moot once the review concludes. In fact, OMB rescinded the memo presumably to moot the specific legal challenge (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) (although here the White House simultaneously maintained the policy, complicating the mootness argument).

- No Harm / Preserving Status Quo: Another defense is that the pause, in theory, preserves the status quo until programs can be assessed. The administration could claim that few if any recipients have a legal right to immediate disbursement of funds in this interim period. For example, if grant funds would normally be drawn down over months, a delay of a couple weeks might not legally injure them (aside from cash flow timing). They would dispute any characterization of vested rights being taken, since ultimately the funds will be disbursed once aligned with priorities (except where legitimately canceled under law). By exempting individual benefit payments and core entitlements, the memo avoided the most clear-cut property interests, focusing on discretionary assistance to organizations or state projects. The government might also assert that plaintiffs lack standing or suffer no irreparable harm from a short pause on new grants (a university that hasn’t yet been awarded a grant cannot claim harm if the award is postponed). This ties into an argument that parts of the pause are committed to agency discretion and not judicially reviewable – decisions on how to allocate discretionary grants often fall under agency expertise and priority-setting, which courts traditionally hesitate to second-guess absent clear standards.

- National Interest and Efficiency: The administration will likely justify the pause as serving the public interest by preventing waste. The memo explicitly mentions stopping funding for “Marxist equity… and green new deal social engineering” that it views as wasteful or contrary to the new policies (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) The President, they argue, has an obligation to ensure taxpayer dollars are spent effectively and consistently with current law and policy. If continuing to fund certain initiatives (started under the prior administration) would undermine new EOs or result in funds being used for soon-to-be-canceled projects, then pausing avoids throwing good money after bad. In legal terms, they might invoke the Antideficiency Act’s allowance for reserves to achieve savings via efficiency (31 USC 1512: Apportionment and reserves) – essentially claiming the pause is to ensure economical use of funds (e.g., not funding grants that might be re-scoped or terminated later). This is arguably within OMB’s apportionment authority. While critics see a political agenda, the administration frames it as a rational means-ends alignment, not a desire to violate the law.

- Support from Case Law: The administration can find some support in the notion that unless Congress has clearly mandated immediate spending, the Executive retains latitude in timing. They could cite Train v. City of New York not as a restriction but as leaving room for “discretion as to the timing of expenditures” (language the government pressed in that case (TRAIN v. CITY OF NEW YORK, 420 U.S. 35 (1975) | FindLaw) though the Court disagreed in context). Also, if no court has definitively ruled on an across-the-board pause like this, the administration can argue there is no precedent directly forbidding it, especially given the unique circumstance of implementing multiple new executive orders at once.

- Counterarguments by Affected Parties: Those challenging the pause advance a combination of legal and equitable arguments against its legality:

- Violation of the Separation of Powers/Purse: As discussed, critics say the pause is an unconstitutional usurpation of Congress’s spending power. No matter how the memo is dressed up, its effect is that the Executive Branch is refusing to execute duly enacted appropriations according to the timelines and purposes Congress set. The quote from Congressman Boyle (Ranking Member, House Budget Committee) captures this view: “Distributing this funding to the American people is a legal requirement… Congress holds the power of the purse… [This pause] leads [to] flagrant violations of the law and blatant disregard for Congress’s constitutional authority over federal spending.” (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) In legal terms, opponents argue the pause is not “to the extent permissible by law” but to the extent of defying the law – pointing out that many programs (education, healthcare, infrastructure grants) have been halted despite Congress having appropriated money for them for FY2025. The absence of explicit statutory authorization for such a blanket review pause means OMB acted beyond its authority. If the President wanted to suspend programs, he should have sought new legislation or used the ICA’s procedures. Opponents likely highlight the historical rarity of such action and compare it to Nixon’s impoundments, which led to rebukes from both Congress and courts. The counter to the “temporary” label is that even a short-lived illegal act is still illegal; plus, there is skepticism that the pause would truly be short (the memo set no firm end date, only that it lasts until OMB issues further guidance after agency reports). There is concern the “temporary” pause could roll into a series of pauses or selective funding denials – effectively a slow-motion impoundment. Thus, challengers push for immediate judicial intervention, as happened on Jan. 28 with the stay.

- APA Violations (Arbitrary and Ultra Vires): Plaintiffs portray the pause as the epitome of arbitrary and capricious agency action. It was abrupt, with no consideration of the impacts on ongoing projects or of alternatives (e.g., targeted review of suspect programs vs. freezing everything). The memo provides colorful rhetoric about “waste” and ideological targets (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) but no substantive analysis of particular programs – it paints with a broad brush. Courts could find this generality and lack of tailoring to be arbitrary. Additionally, challengers note the pause conflicts with the agencies’ own missions and prior findings (for instance, if an agency had awarded a grant because it found the project meritorious and in the public interest, halting it on ideological grounds without evaluation contradicts that record). This kind of unexplained reversal can be deemed arbitrary under the State Farm standard (agency action is arbitrary if the agency entirely fails to consider an important aspect of the problem). The memo’s exclusion of “assistance… to individuals” and certain benefits (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) also implicitly acknowledges that stopping funds hurts people; yet it offers no rationale why other recipients (states, nonprofits, universities) can be subjected to harm. On the “ultra vires” front, plaintiffs contend OMB simply has no legal authority to issue binding directives of this magnitude to independent agencies or to override existing grant regulations. OMB memos are normally guidance, but here it functioned as a command – arguably without an underpinning rule or statute. Therefore, it should be set aside as agency action in excess of authority (5 U.S.C. §706(2)(C)).

- Harm and Reliance Interests: A strong equitable argument is the harm caused to beneficiaries and recipients. Many federal grants fund critical services – e.g., public health initiatives, university research, infrastructure projects. The pause “jeopardizes critical programs that millions…depend on” (Boyle Statement on White House Attempt to Pause Federal Funding | House Budget Committee Democrats) Nonprofit and state plaintiffs have documented how even a short funding interruption can cause layoffs, stoppage of services, or inability to meet matching requirements (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) These real-world impacts bolster the claim that the pause is not just a harmless delay but an action with significant consequences, which by law required a more thorough decision-making process and likely congressional approval. From a due process and fairness standpoint, recipients argue it is profoundly unjust for the rules of the game to change overnight with no notice. Many had applied for grants or planned budgets expecting funds to flow as scheduled; the government induced reliance and then pulled back without legal cause. This can be framed as arbitrary, but also as a violation of equitable estoppel principles (though estoppel against the government is hard to win, courts are sympathetic when agencies act in a seemingly bad faith manner).

- Precedent and Rule of Law: Opponents invoke the principle that no one, not even the President, is above the law. Historical precedent after precedent has constrained executive impoundment. They point out that since the ICA of 1974, Presidents have largely complied with sending rescission or deferral messages rather than outright freezing funds. By bypassing these procedures, the current pause sets a dangerous precedent, essentially allowing an administration to ignore appropriations for any reason (or under the vague guise of “review”). This undermines the rule of law and the finely balanced budget process. In court, this translates to arguments that allowing the pause to stand would render the ICA a dead letter and invite future abuse (e.g., today it’s “woke” programs, tomorrow a different President might freeze funds for, say, border security or defense projects – a slippery slope).

- Constitutional Claims: Finally, challengers bolster their case with constitutional claims like the First Amendment. If they can show that the motive and effect of the pause are to single out certain viewpoints (e.g., cutting funding to organizations that support LGBTQ+ or climate initiatives because the administration disfavors those causes), a court could find a First Amendment violation. The memo’s own language is evidence of viewpoint targeting (Microsoft Word – M-25-13 Temporary Pause to Review Agency Financial Assistance Programs – final_SB) While the government can choose not to fund certain activities, it cannot do so solely to silence a viewpoint. Even if a court doesn’t reach the First Amendment claim (often courts prefer to decide on statutory grounds), its presence adds moral weight to the argument that the pause is improper. State plaintiffs also add that the pause might violate the Tenth Amendment by commandeering state budgetary processes (states expecting federal funds had to scramble).

Conclusion: In a formal legal assessment, the temporary pause on federal grants and assistance (OMB M-25-13) appears to rest on shaky legal ground. While the Executive has some authority to coordinate and review spending, the breadth of the freeze and its indiscriminate nature conflict with core legal constraints – notably Congress’s power of the purse and the Administrative Procedure Act’s demands for reasoned, lawful agency action. Past precedent and the Impoundment Control Act underscore that the President cannot unilaterally withhold appropriated funds absent specific statutory authority. Grant recipients and state beneficiaries have viable claims under the APA and Constitution to challenge the pause, as evidenced by immediate court intervention halting the freeze on existing awards (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) On the other hand, the administration can argue that it tailored the pause to comply with the law (“to the extent permissible”) and that it serves legitimate administrative ends in line with the President’s policymaking prerogatives. Ultimately, a court reviewing the pause would weigh these arguments. Given the strong judicial and congressional precedents affirming that executive agencies must execute funding laws as written, the more persuasive view is that the pause – if maintained – would likely be struck down as unlawful. Recipients of federal funds do have recourse through both legal action and political channels to ensure that appropriated monies are released. Any future attempts by the executive branch to suspend congressionally approved funding will likely be met with similar legal challenges and require clear legal justification to survive. The swift rescission of OMB M-25-13 and the administration’s clarification suggest recognition of these legal vulnerabilities (OMB Memorandum on Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs | NAFSA) (The OMB Issued a Memo Freezing Federal Financial Assistance. And Then Rescinded the Memo, But Not the Freeze. Confused? Read On | Venable LLP – JDSupra) In sum, while a President may pause to review, he must ultimately proceed to spend as directed by law – or risk violating fundamental tenets of our constitutional and administrative law system.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog