In law practice today, technology is no longer optional — it’s essential. As practicing attorneys increasingly rely on technology tools to serve clients, conduct research, manage documents and streamline workflows, the question is often debated: Are law schools adequately preparing students for this reality?

Unfortunately, for the majority of law schools, the answer is no. But that only begs the question: What should they be doing?

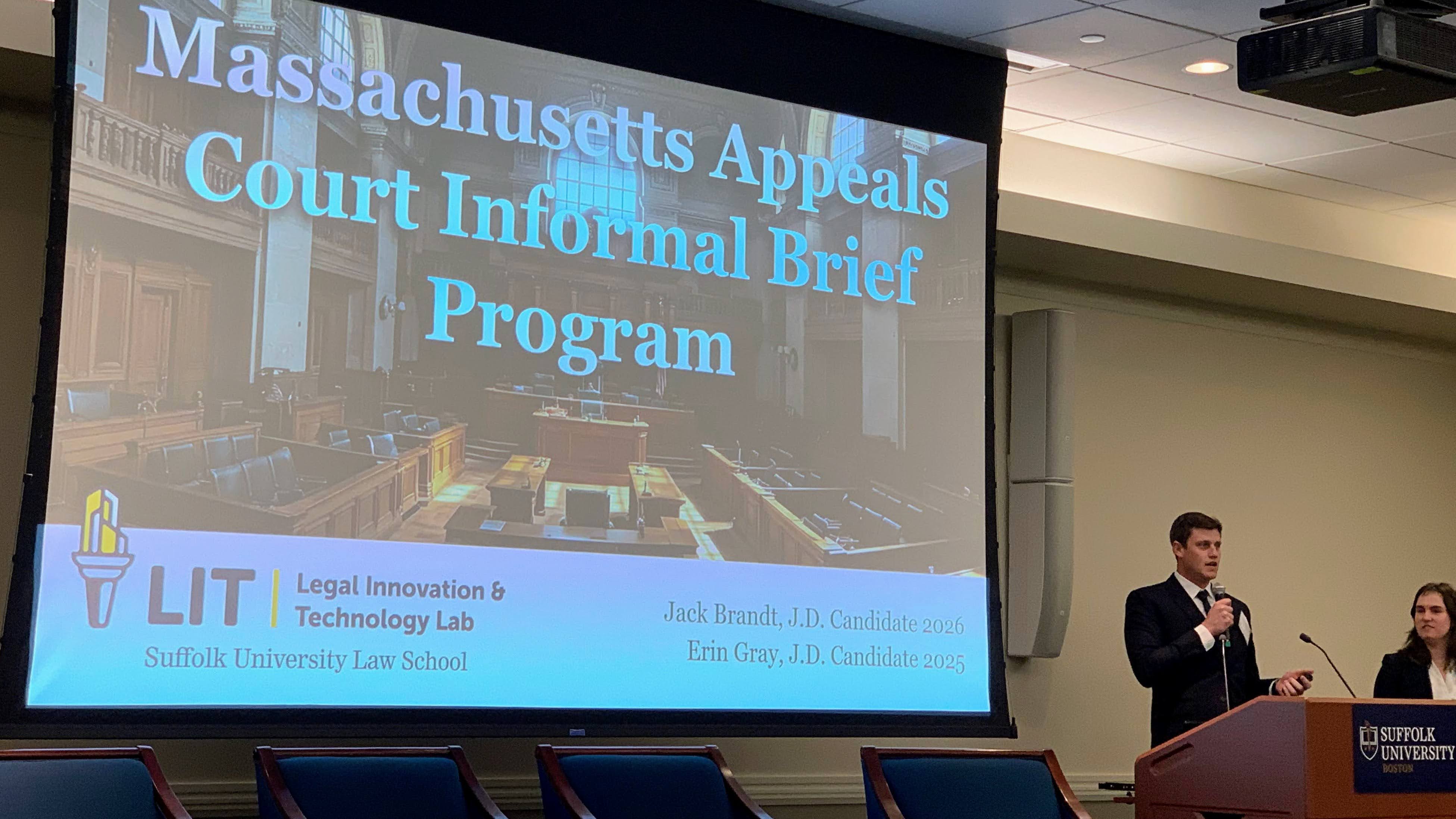

A coincidence of events last week had me thinking about law schools and legal tech, chief among them my attendance at LIT Con, Suffolk Law School’s annual conference to showcase legal innovation and technology — with a portion of it devoted to access-to-justice projects developed by Suffolk Law students themselves.

Suffolk Law stands out as a national leader in legal technology, spearheaded by its dean Andrew Perlman, the codirectors of its Legal Innovation & Technology Lab (LIT Lab) David Colarusso and Quinten Steenhuis, and the director of its Legal Innovation & Technology Center Dyane O’Leary.

(In the photo above from last week’s LIT Con, Suffolk Law students Jack Brandt and Erin Gray discuss their project with the Massachusetts Appeals Court to develop an informal brief program for self-represented litigants.)

Several other law schools also stand out for their legal tech programs, such as Brigham Young University and its LawX program, which follows a similar model as Suffolk, engaging students in designing solutions to specific legal problems. Of course, schools such as Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, Stanford Law School, and Chicago-Kent College of Law have long been leaders in integrating technology into legal education.

But what of law schools that have not yet started down this path or are only just beginning? What should they be doing?

While I don’t claim the credentials of a career academic, I do have many years’ experience working at the intersection of law and technology, and that has given me some perspective on this question. I have come to believe that a basic law school framework for teaching students about technology involves a tiered approach I think of as the three Cs.

The First C: Technology Competence

The foundation of legal technology education begins with basic competence. This isn’t merely a pedagogical preference — it’s an ethical imperative. Most state bars have adopted some version of the ABA Model Rules’ duty of technology competence, requiring lawyers to understand the benefits and risks of relevant technology.

Law schools, I believe, have a responsibility to provide students with a basic grounding in technology by ensuring that their graduates understand:

- The technology tools commonly used in law practice.

- The ethical implications of technology use in legal representation.

- How clients use technology in ways that might affect their legal matters.

- Basic cybersecurity and client confidentiality issues in a digital world.

This first level is fundamentally curricular. Beyond traditional doctrinal classes, law schools should develop courses specifically addressing technology in legal practice. Whether integrated into professional responsibility coursework or offered as standalone electives, these courses provide the minimal baseline of knowledge every law student needs before entering practice.

The Second C: Technology Curiosity

While competence focuses on the baseline requirements, curiosity elevates technology from necessity to opportunity. The second C is about engendering genuine enthusiasm for technology’s potential to transform legal practice for the better.

Technology curiosity means fostering an environment where students become interested in — maybe even excited about — how technology can:

- Improve the delivery of services to clients.

- Make legal services more accessible and affordable.

- Drive the next generation of law practice.

- Create new career opportunities at the intersection of law and technology.

One effective approach that I’ve observed for sparking this kind of curiosity is bringing innovators directly to students through speaker series and workshops. By exposing students to practicing attorneys who use technology creatively, legal tech entrepreneurs, access-to-justice advocates, and others pushing boundaries in the field, law schools can inspire students to think beyond merely competent use of existing tools.

When students develop genuine curiosity about legal technology, they begin to ask crucial questions — questions that cause them to challenge the status quo and that prepares them not just for law practice as it exists today, but as it will evolve throughout their careers. In fact, that curiosity can drive them to be leaders in that evolution.

The Third C: Technology Capability

The final and most advanced C moves from knowledge and interest to active creation. Technology capability means giving students hands-on opportunities to develop technological solutions to legal problems.

This approach typically takes the form of innovation labs or clinics where students:

- Identify specific challenges in legal service delivery.

- Apply design thinking methodology to develop potential solutions.

- Create working prototypes of applications or systems.

- Test and refine their creations with actual users.

I’m not suggesting every law student needs to become a programmer, though basic coding skills can certainly be valuable. Rather, these innovation environments teach students to collaborate across disciplines, manage technology projects, and bridge the gap between legal needs and technological possibilities.

Some law schools have the advantage of tapping into broader university resources, allowing them to create these programs in collaboration with computer science, business or design departments. But even without these partnerships, schools can create meaningful innovation experiences through carefully structured projects and appropriate technical support.

Implementing the Three Cs

For a law school looking to expand its legal technology training, it certainly need not jump into implementing all three Cs simultaneously. Rather, the more sensible approach might be a graduated one, such as:

- Year one: Introduce a required course on technology competence for all students.

- Year two: Launch a speaker series bringing innovators to campus.

- Year three: Create a small innovation lab or clinic for interested students.

- Year tour: Expand to cross-disciplinary collaboration with other departments.

The appeal of this framework is its scalability. Even schools with limited resources can begin with basic competence training and gradually build toward more ambitious goals.

Creating Tech-Savvy Leaders

As I say, I’m no academic. But I do know that the legal profession has a reputation for having been slow to embrace technological change, and that law schools have been complicit in that.

That luxury no longer exists. As clients demand greater efficiency and accessibility, as the access-to-justice crisis worsens, and as technology continues to transform how legal services are delivered, law schools can no longer wait to adapt their curricula accordingly.

These three Cs — Competence, Curiosity and Capability — offer a common-sense, practical approach by which legal educators can ensure their graduates not only meet ethical obligations regarding technology, but are positioned to lead legal innovation. The goal isn’t to turn lawyers into technologists, but to create technology-savvy lawyers who understand how to leverage digital tools to better serve their clients and society.

The future of legal practice will belong to those who can bridge the divide between traditional legal thinking and technological opportunity. Law schools that embrace this reality today will produce the legal leaders of tomorrow.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog